In an extraordinary milestone for biomedical science, the UK Biobank has announced the completion of its ambitious imaging study, having successfully scanned the brains, hearts, and other vital organs of 100,000 volunteers. Spanning over a decade, this unprecedented initiative now provides researchers worldwide with the most comprehensive imaging dataset ever assembled, opening new frontiers in the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of a vast range of diseases.

A Decade-Long Ambition Realised

The UK Biobank Imaging Study began in 2014 as a significant expansion of the original UK Biobank cohort, which had already recruited 500,000 individuals between the ages of 40 and 69 from across the UK between 2006 and 2010. The aim of the imaging enhancement was to gather detailed, high-resolution images of the brain, heart, bones, and abdomen in a subset of 100,000 participants. The final scan was completed in 2025, marking the end of an 11-year data collection effort unmatched in scope and precision.

From the outset, the vision was bold. By combining imaging data with genetic, biochemical, lifestyle, and health records, the project aimed to create a resource that could transform our understanding of how diseases develop and progress over time. It was hoped that such a resource would not only help to identify early warning signs of illness but also support the discovery of new treatments and interventions long before symptoms manifest.

Cutting-Edge Imaging Across the UK

Participants were invited to attend one of four dedicated imaging centres located in Newcastle, Reading, Stockport, and Bristol. Each centre was equipped with a suite of cutting-edge scanning technologies, including 3T MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) scanners, DXA (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry) for bone density assessment, and ultrasound machines.

The standard imaging protocol lasted about four hours and included:

- Brain MRI: capturing both structural and functional aspects of the brain, including white matter integrity, grey matter volume, and resting-state connectivity.

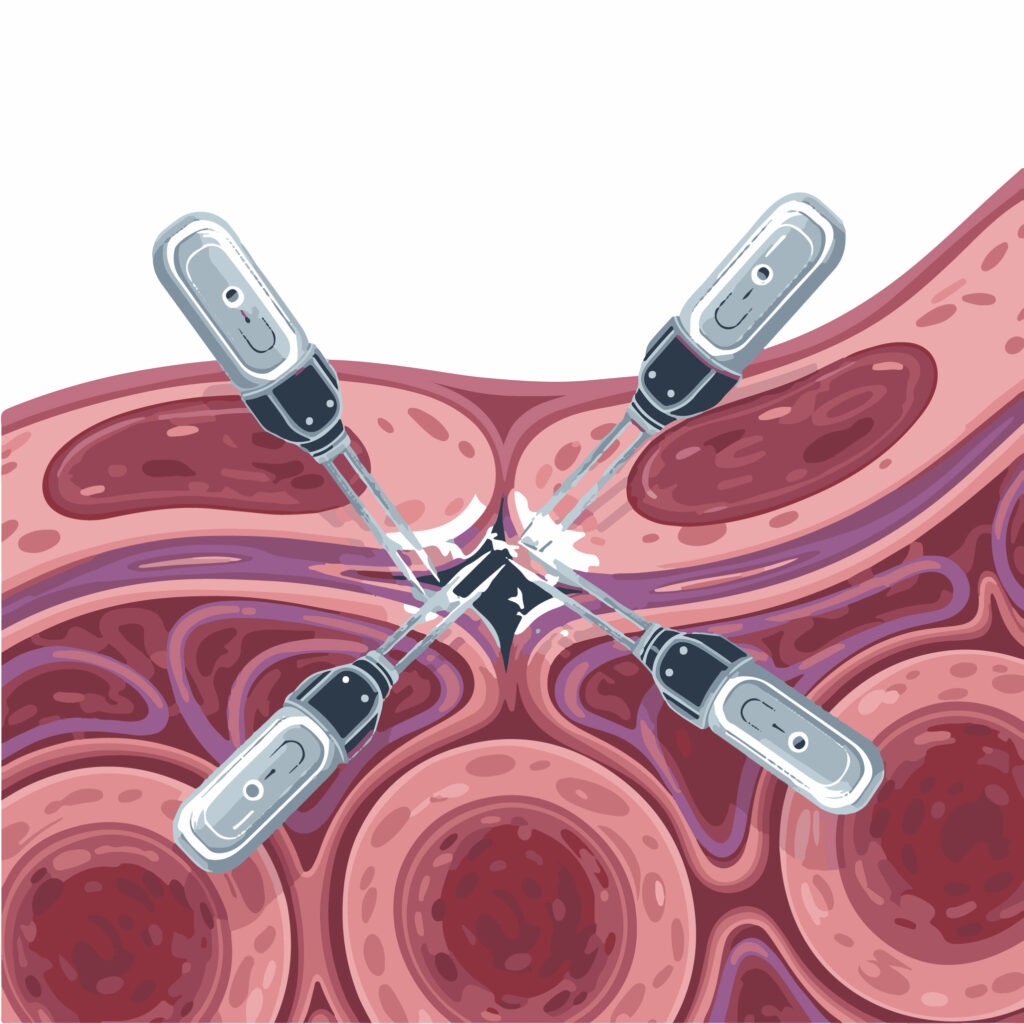

- Cardiac MRI: offering a detailed view of heart structure, function, and blood flow.

- Abdominal MRI: focusing on organs such as the liver, pancreas, and kidneys.

- DXA scan: measuring bone density and body composition.

- Carotid ultrasound: assessing plaque build-up and artery wall thickness, important markers for cardiovascular disease.

The study also piloted imaging of the spine and musculoskeletal system, expanding the potential research applications further.

The Role of Volunteers

None of this would have been possible without the extraordinary commitment of the UK Biobank’s volunteer participants. Each individual took part on a purely altruistic basis, with no direct medical benefit offered. Participants were informed that they would not routinely receive feedback on their scans unless something potentially serious was spotted incidentally — a policy that led to a small number being referred to their GPs for follow-up, though the project remained research-focused.

The dedication of these volunteers, who gave up their time to attend scanning sessions and complete regular health and lifestyle updates, has enabled the creation of a longitudinal dataset of immense scientific value.

Scientific and Global Impact

Researchers around the world are already using the imaging data collected to investigate an extraordinary range of questions. The open-access nature of the UK Biobank resource — made available to bona fide researchers in both academic and commercial settings — has democratised health research and accelerated discoveries in numerous fields.

Key breakthroughs made possible by the imaging study include:

- Early biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease: Using brain scans, researchers have identified subtle structural changes in individuals with a genetic predisposition to Alzheimer’s decades before symptoms appear.

- Insights into cardiovascular ageing: Cardiac MRI data have allowed scientists to map out how heart function changes with age and how these changes differ depending on lifestyle factors, such as physical activity, smoking, and diet.

- Understanding fat distribution and metabolic risk: Abdominal MRI data have revealed that fat stored around organs (visceral fat) correlates more strongly with diabetes and heart disease risk than general measures of obesity, such as BMI.

- Genetic studies of organ structure: By integrating imaging with genetic data, new loci associated with brain and heart structure have been identified, offering insights into the hereditary basis of disease.

These examples represent just a fraction of the studies already published using UK Biobank imaging data. As analysis deepens, the dataset is expected to contribute to many more areas, including mental health, stroke, musculoskeletal, and autoimmune diseases.

The Power of Multimodal Data

What makes the UK Biobank Imaging Study uniquely powerful is its integration with the wider Biobank dataset. In addition to imaging, each participant has contributed:

- Biological samples (blood, urine, saliva) for biomarker and genomic analysis

- Detailed lifestyle questionnaires covering diet, physical activity, sleep, and environmental exposures

- Cognitive function tests

- Long-term health outcomes through linkage to NHS records, including hospital visits, prescriptions, cancer registries, and death certificates

This multi-layered data structure enables researchers to move beyond correlations and begin to uncover causal relationships. For example, suppose a particular brain change observed on MRI is associated with both a genetic variant and a specific health outcome. In that case, the evidence for a causal pathway becomes significantly stronger.

Moreover, the longitudinal nature of the study — with many participants now followed for over 15 years — allows for the examination of how early life exposures and lifestyle choices impact disease development decades later.

Addressing Challenges in Health Inequality

Although the study has achieved remarkable depth and breadth, it is not without limitations. One of the main criticisms of the UK Biobank, including its imaging component, has been its lack of diversity. The cohort is not fully representative of the UK population, with an overrepresentation of white, relatively healthy individuals from more affluent backgrounds.

The UK Biobank has acknowledged this and is working to address it through targeted outreach and future projects, but it remains a consideration when interpreting results. Researchers are encouraged to account for these demographic imbalances and to complement findings with data from more diverse cohorts when possible.

Despite this, the scale and standardisation of the imaging dataset make it an indispensable tool for hypothesis generation and testing, particularly in well-resourced health systems with similar demographics.

Preparing for the Future

With the scanning phase now complete, the focus shifts to data analysis and the introduction of new enhancements. Plans are in place to continue following up participants through electronic health records, and additional biomarker assays are underway, including proteomics, metabolomics, and microbiome analyses.

Artificial intelligence and machine learning methods are being increasingly applied to imaging data, with the goal of automating feature extraction and identifying patterns beyond human perception. These technologies have already been used to develop ‘biological age’ estimates based on organ images — tools that could help identify individuals at higher risk of age-related diseases.

There are also discussions about launching new imaging centres or repeat scans in a subset of participants to examine changes over time. Repeat imaging would be especially valuable for studying disease progression and the long-term effects of interventions such as medications, surgery, or lifestyle changes.

International Collaboration and Influence

The UK Biobank Imaging Study has set a new global standard for large-scale population imaging. It has inspired similar initiatives in other countries, including:

- The Million Veteran Program in the United States

- The German National Cohort (NAKO)

- The Canadian Partnership for Tomorrow’s Health (CanPath)

However, the UK Biobank remains unique in its scale, accessibility, and integration across data types. It serves not only as a research platform but also as a model of how large-scale health data projects can be conducted ethically, efficiently, and collaboratively.

Ethical Oversight and Public Trust

Maintaining public trust has been central to the success of the UK Biobank. From the beginning, the project has operated under rigorous ethical standards, with oversight from an independent ethics and governance council. Data is de-identified, securely stored, and made available only to approved researchers for health-related purposes.

Participants are kept informed through regular updates and have the option to withdraw at any time. This transparency, combined with the altruistic spirit of the volunteers, has helped the project maintain high levels of public support even as it enters more complex areas of data science and genomics.

Conclusion

The completion of the UK Biobank’s imaging study is more than a technical milestone; it is a landmark in the history of biomedical research. In scanning the organs of 100,000 volunteers, the project has created a resource that will continue to shape our understanding of human health for decades to come.

With over 30 million images already collected and more than 10,000 researchers accessing the resource globally, the actual impact of this achievement is only beginning to unfold. It is a testament to what can be accomplished when vision, technology, and public goodwill come together in service of science.

As medicine moves increasingly towards personalisation and prevention, datasets like the UK Biobank imaging study will be essential. They allow us not only to understand what is happening inside the body but also to predict what might happen next — and crucially, how to intervene before it does.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is provided for general informational purposes only and does not constitute medical, legal or professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information presented, Open Medscience makes no guarantees regarding its completeness or correctness. Reliance on any information herein is at your own risk. Readers seeking medical guidance should consult a qualified healthcare professional before making any decisions based on the material discussed. Mention of specific studies, organisations or products does not imply endorsement by Open Medscience. Under no circumstances will Open Medscience, its authors or contributors be liable for any loss or damage arising from the use of, or reliance on, the information contained in this article.

home » blog » medical imaging news »