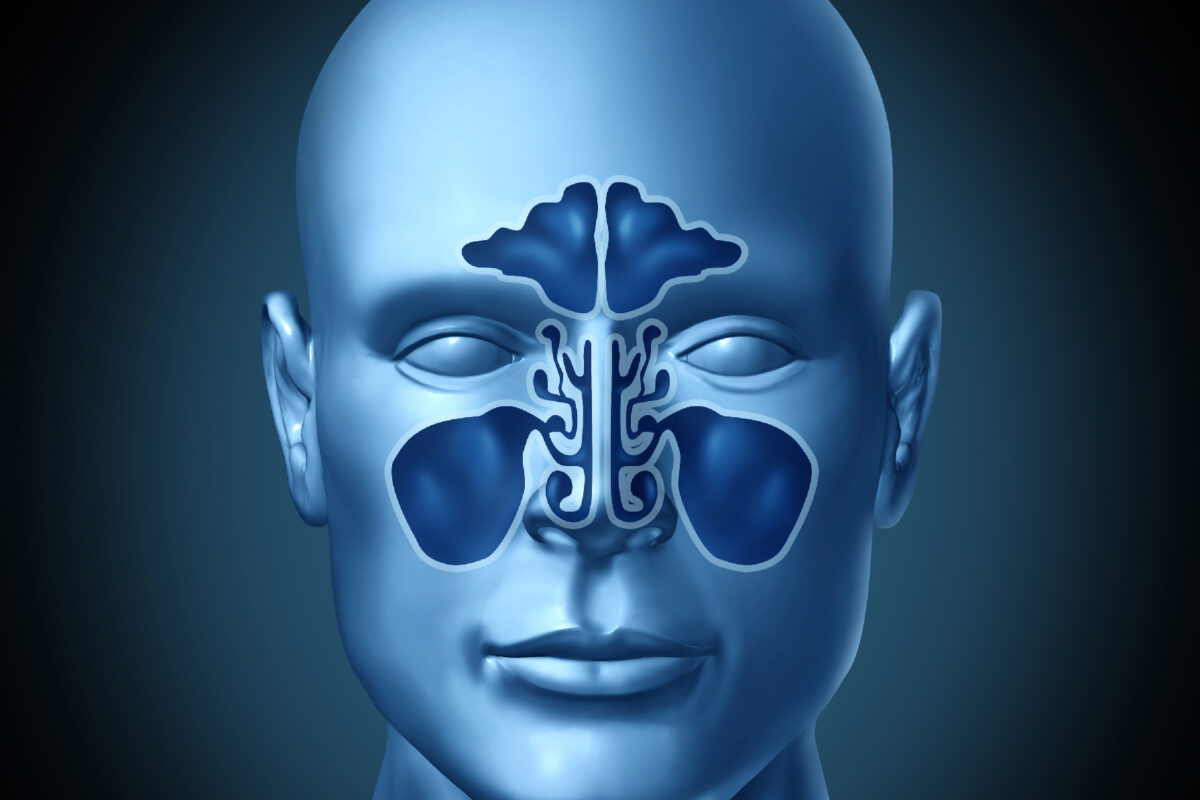

Over the last decade, medical imaging of the nose and paranasal sinuses has moved far beyond simple X-rays to become a core part of ear, nose and throat practice. From chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps to trauma, tumours and post-viral loss of smell, imaging now supports diagnosis, treatment planning, surgery and follow-up. At the same time, pressure to reduce radiation dose and waiting times has pushed clinicians to rethink how they acquire and use images.

This article tours recent developments in nasal imaging, focusing on refinements in CT and cone-beam CT, new uses of MRI, emerging roles for ultrasound, the growth of artificial intelligence and radiomics, advances in imaging of sinonasal tumours and skull-base disease, and the rise of image-guided and augmented-reality sinus surgery.

CT, cone-beam CT and the drive towards ultra-low-dose imaging

Conventional multi-slice CT remains the workhorse for imaging the paranasal sinuses. It is fast, widely available, and excellent for visualising bony anatomy and the air–soft-tissue interfaces that define sinus disease. Concern about cumulative radiation exposure has encouraged the development of techniques that preserve diagnostic quality while cutting dose.

One important shift has been the increasing use of cone-beam CT (CBCT) for nasal and mid-face imaging. Originally introduced in dental and maxillofacial practice, CBCT scanners now offer high-resolution volumetric scans with thin reconstructions that are ideal for assessing nasal fractures, septal deviations, osteomeatal complex anatomy and the extent of chronic sinusitis. In many protocols, the radiation dose is lower than that of standard sinus CT, which is attractive for younger patients and those who need repeated imaging.

Alongside CBCT, new generations of CT hardware are also changing the picture. Photon-counting CT detectors can capture individual X-ray photons and sort them by energy, improving spatial resolution and contrast while enabling dose reduction. Early work in the paranasal sinuses suggests that photon-counting CT can match, or even surpass, CBCT for visualising fine bony structures and mucosal disease, with better soft-tissue contrast and flexible post-processing. Radiology departments are refining sinus CT protocols using tin filtration, iterative reconstruction and careful optimisation of tube current and voltage, allowing “as low as diagnostically acceptable” doses without sacrificing the details that surgeons rely on.

The net result is a toolkit that can be tailored to the clinical question. A patient with minor trauma may be scanned with a low-dose CBCT in an outpatient setting, whereas complex revision surgery planning might still require a high-quality multi-slice or photon-counting CT study.

MRI of the sinuses and the olfactory system

MRI has traditionally played a supporting role in sinonasal imaging, reserved for cases in which soft-tissue contrast is critical: suspected tumours, skull-base involvement, orbital complications, or intracranial spread. In recent years, that boundary has begun to blur.

One important development is the growing use of lower-field MRI systems, including 0.5 T scanners, to evaluate inflammatory sinus disease. Although bone is better assessed with CT, modern low-field MRI can depict mucosal thickening, polyps, and fluid levels with a level of detail that is often sufficient for medical management, and crucially, it does so without ionising radiation. For selected patients, particularly children and younger adults with recurrent sinus symptoms, MRI may offer a safe alternative when fine bony detail is not essential.

At the other end of the spectrum, ultra-high-field MRI at 7 T has opened a window onto structures that were previously very difficult to see. The olfactory bulbs, tracts and even the tiny nervus terminalis can now be visualised in much finer detail. This has become especially relevant in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, where many patients developed persistent anosmia or parosmia. High-resolution structural imaging, diffusion tensor imaging and functional MRI are being used to study volume loss, microstructural change and altered connectivity in olfactory pathways and related brain networks.

Researchers are also using advanced MRI to examine CSF flow and drainage in the region around the cribriform plate and olfactory clefts. By tracking the movement of contrast agents, they can map pathways that may be important for drug delivery through the nose and for the clearance of waste products from the brain.

Ultrasound and point-of-care assessment

Compared with CT and MRI, ultrasound seems an unlikely candidate for nasal imaging. Bone strongly reflects sound waves, limiting penetration, and air in the nasal cavities further complicates matters. Nevertheless, high-frequency linear probes can provide informative images of the nasal bones and surrounding soft tissues.

Current research is exploring the use of bedside ultrasound to diagnose nasal fractures in emergency settings. Ultrasound can identify cortical disruptions and step deformities at the bedside and without radiation. Comparative studies aim to show when ultrasound can reliably replace CT for simple fractures, reserving cross-sectional imaging for complex injury patterns or patients being considered for surgical repair.

Artificial intelligence, radiomics and automated analysis

The most dramatic changes in sinonasal imaging may come not from new scanners, but from new ways of interpreting the images we already have. Artificial intelligence and radiomics are increasingly automating labour-intensive tasks, extracting subtle imaging biomarkers, and supporting clinical decisions.

In chronic rhinosinusitis, radiologists and surgeons commonly use the Lund–Mackay scoring system to quantify disease burden on CT. Manually assigning these scores can be time-consuming and prone to inter-observer variation. Deep learning models based on convolutional neural networks can now segment the paranasal sinuses automatically and generate Lund–Mackay scores that closely match expert readings. In practice, this could streamline reporting, standardise assessments and free specialists to focus on more nuanced aspects of imaging.

Beyond simple scoring, AI is being trained to recognise patterns associated with particular disease endotypes. In chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, for example, eosinophil-rich inflammation carries a higher risk of recurrence and may respond differently to biologic therapies. Studies suggest that texture and shape features on CT, sometimes in combination with clinical data, can help models predict these endotypes and estimate the likelihood of response to surgery or targeted drugs.

Radiomics, the quantitative analysis of large numbers of imaging features, is also being applied to sinonasal tumours. Tumours that appear broadly similar on conventional CT or MRI can exhibit very different behaviour. By capturing subtle variations in intensity, heterogeneity and shape, radiomic models aim to distinguish benign from malignant lesions, predict aggressiveness and help stratify patients for more or less intensive treatment and follow-up. Validation and integration into clinical workflows will be crucial.

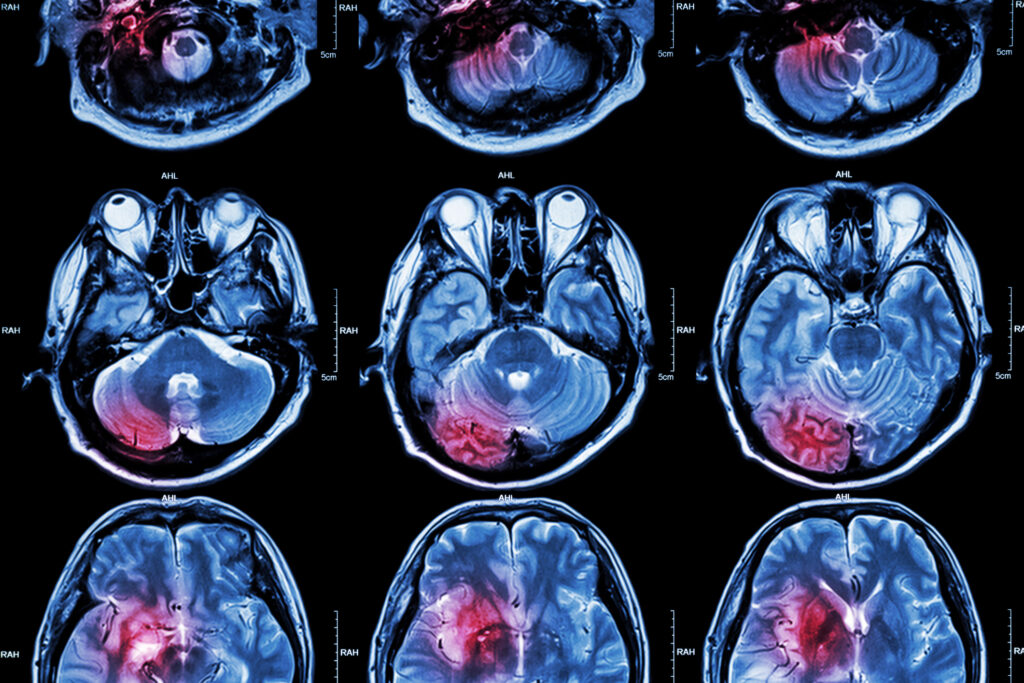

Imaging of sinonasal tumours and skull-base disease

For sinonasal and skull-base tumours, progress has come through refinement and integration rather than completely new modalities. Modern protocols combine the strengths of CT, MRI and PET to answer specific questions.

High-resolution CT still provides the best assessment of bone. It is used to map bony destruction and remodelling, and to assess the relationship of tumours to critical structures such as the orbit, the skull base, and the internal carotid arteries. MRI complements this by offering superior soft-tissue contrast, highlighting perineural spread, intra-orbital extension, dural involvement and intracranial invasion. Diffusion-weighted imaging and dynamic contrast sequences provide additional information on tissue cellularity and vascularity.

Positron emission tomography, typically combined with CT, contributes functional data, helping to stage disease, detect nodal or distant metastases and assess treatment response. In some tumour types, such as esthesioneuroblastoma or other neuroendocrine lesions, tracers that target somatostatin receptors can improve sensitivity and guide radionuclide therapy.

Taken together, these modalities support a multidisciplinary approach in which surgeons, oncologists, and radiologists collaborate closely. Detailed pre-operative imaging allows surgeons to choose between purely endoscopic, combined endoscopic–open or more extensive craniofacial approaches, and guides radiotherapy planning with millimetre precision.

Image-guided navigation and augmented-reality sinus surgery

Image-guided navigation systems register pre-operative CT or MRI datasets to the patient’s anatomy and track surgical instruments in real time, displaying their position on multiplanar reconstructions. For complex frontal sinus, sphenoid or skull-base work, this “GPS for the sinuses” improves orientation, particularly in distorted revision anatomy, and provides reassurance when operating close to the orbit or carotid artery.

Newer systems are making this technology more intuitive. Improved registration techniques reduce errors between the virtual model and the patient, while faster processors and better displays allow smoother interaction. Augmented-reality overlays can project key anatomical landmarks or planned surgical routes onto the endoscopic view, fusing pre-operative planning with intra-operative decision-making. Many centres now routinely use navigation for advanced cases, and evidence suggests it reduces complications and helps surgeons operate with greater confidence.

What this means for patients and clinicians

For patients, these advances translate into safer imaging with lower radiation doses, more accurate diagnoses, and better-targeted treatments. Someone with long-standing sinus problems may now receive a low-dose CT or CBCT scan that clearly defines the anatomy with minimal exposure, followed by endoscopic surgery guided by a navigation system. Another person with unexplained loss of smell after a viral infection might undergo a high-resolution MRI that not only excludes structural lesions but also reveals changes in the olfactory bulbs and related brain networks.

For clinicians, the challenge is to stay abreast of these developments and integrate them sensibly into practice. Not every patient needs cutting-edge AI analysis or ultra-high-field MRI, and access to the latest scanners remains uneven. However, the direction of travel is clear: nasal and sinus imaging is becoming more quantitative, more personalised and more tightly woven into surgical planning.

As hardware continues to evolve and AI systems mature, the nose and paranasal sinuses are likely to become one of the best-understood anatomical regions from an imaging perspective. That is good news for the many people living with sinus disease, smell disorders, or complex nasal tumours, and for the clinicians striving to treat them with greater precision and fewer side effects.

Q and A on Recent Developments in Nasal and Sinus Imaging

Q: Why has imaging of the nose and sinuses advanced so much in recent years?

A: Conditions such as chronic rhinosinusitis, nasal polyps, trauma, tumours and post-viral loss of smell affect large numbers of patients and often require detailed anatomical information to guide treatment and surgery. At the same time, there is pressure to minimise radiation exposure and improve diagnostic accuracy. This combination has encouraged innovation in scanning technology, image processing and clinical applications.

Q: What are the main improvements in CT and cone-beam CT for the sinuses?

A: Conventional multi-slice CT remains central to sinus imaging because it provides sharp visualisation of bone and air-soft tissue boundaries. Recent progress has focused on cutting radiation dose while preserving diagnostic value. Cone-beam CT (CBCT) has become more common for nasal and mid-face imaging. It produces thin, high-resolution reconstructions that are well suited to trauma assessment, septal deviation, osteomeatal anatomy and chronic sinusitis. In many situations, the dose is lower than standard CT, which benefits patients who may require repeated scans.

Alongside CBCT, new scanner hardware has appeared, including photon-counting CT systems. These detectors register individual X-ray photons and sort them by energy, improving spatial resolution and contrast while allowing dose reduction. Radiology teams are also fine-tuning sinus CT protocols using filtration, iterative reconstruction and careful control of scanner settings. The outcome is a set of options that can be matched to the clinical question, ranging from low-dose outpatient CBCT for minor injuries to high-detail CT for complex surgical planning.

Q: Is MRI being used more often for nasal and sinus problems?

A: Yes, although CT is still preferred for detailed bone assessment, MRI is now playing a broader role. Traditionally, it was reserved for tumours, orbital complications and skull-base involvement. Newer approaches have widened their use.

Lower-field MRI systems, including 0.5 T scanners, can show mucosal thickening, polyps and sinus fluid without radiation exposure, which may be helpful in selected inflammatory conditions. At the other end of the spectrum, ultra-high-field 7 T MRI allows clinicians to visualise the olfactory bulbs, tracts and related structures with far greater clarity. This has been especially useful in research on post-viral and COVID-related smell disorders, where structural and functional MRI techniques are helping to characterise changes in the olfactory system.

MRI is also being used to study fluid movement around the cribriform plate and olfactory clefts, supporting research on nasal drug-delivery pathways and neurological waste-clearance mechanisms.

Q: Can ultrasound really be used to examine the nose?

A: Ultrasound has a limited role compared with CT and MRI because bone reflects sound waves and air disrupts the signal. Even so, high-frequency ultrasound can show the nasal bones and adjacent soft tissues. Current studies are exploring its value in diagnosing nasal fractures in emergency settings. It offers a rapid, radiation-free bedside tool that may safely replace CT in straightforward injuries, while reserving cross-sectional imaging for complex trauma or surgical planning.

Q: How is artificial intelligence influencing sinonasal imaging?

A: Artificial intelligence (AI) and radiomics are changing how scans are interpreted rather than how they are acquired. In chronic rhinosinusitis, clinicians often use the Lund–Mackay scoring system to quantify disease on CT. Manual scoring takes time and varies between readers. Deep learning models can now automatically segment the sinuses and generate scores that closely align with expert assessment, improving consistency and efficiency.

AI is also being trained to recognise imaging features associated with specific inflammatory endotypes, such as eosinophilic disease linked to nasal polyps. These models may help predict recurrence risk and likely response to surgery or biologic therapy. Radiomics extends this idea further in tumour imaging by extracting large numbers of quantitative features to distinguish between lesions that may appear similar to the human eye. Although these tools still require validation, they point towards more personalised care.

Q: What progress has been made in imaging sinonasal tumours and skull-base disease?

A: Rather than introducing a completely new modality, progress has come from integrating existing ones more effectively. High-resolution CT maps bone destruction, remodelling and proximity to critical structures such as the orbit and internal carotid arteries. MRI adds superior soft-tissue detail, highlighting perineural spread, intra-orbital extension, dural contact and intracranial involvement. Diffusion-weighted and dynamic contrast imaging contribute further tissue characterisation.

PET/CT provides functional information that supports staging, surveillance, and assessment of treatment response. In certain tumour types, receptor-targeted tracers can improve sensitivity and help guide therapy. Multidisciplinary teams use this combined information to select surgical approaches, plan radiotherapy accurately and individualise follow-up.

Q: How have imaging innovations influenced sinus and skull-base surgery?

A: Imaging is no longer only a diagnostic tool; it is integrated directly into the operating theatre. Image-guided navigation systems register pre-operative CT or MRI data to the patient and track surgical instruments in real time. This allows surgeons to see exactly where they are within complex anatomy, which is especially helpful in revision cases and procedures near the orbit or major vessels.

Newer systems improve registration accuracy and responsiveness, while augmented-reality overlays can project anatomical landmarks or planned routes onto the endoscopic view. These developments support safer dissection, clearer orientation and greater confidence during advanced endoscopic procedures.

Q: What do these changes mean for patient care?

A: Patients benefit from imaging that is safer, more precise and better integrated with treatment. Lower-dose CT and CBCT reduce radiation burden while still providing the anatomical clarity required for decision-making. MRI offers radiation-free assessment in selected inflammatory cases and deeper insight into smell disorders and skull-base pathology. AI-assisted analysis has the potential to standardise reporting and support more tailored therapeutic choices. In surgery, navigation and augmented-reality tools help reduce complications and improve operative planning.

Q: Are these technologies available everywhere yet?

A: Access varies between hospitals and health systems. Photon-counting CT and 7 T MRI, for example, are still emerging technologies found mainly in specialist centres. CBCT, advanced CT protocols, and navigation systems are more widely available, though not universally. As costs fall and evidence accumulates, uptake is likely to expand, but clinicians still need to select the most appropriate tool within the resources of their local setting.

Q: How should clinicians decide which imaging method to use?

A: The choice depends on the clinical question. For inflammatory sinus disease requiring surgical planning, CT or CBCT is usually preferred because of its ability to display bone and ostiomeatal anatomy. For suspected tumour, skull-base involvement or orbital complications, MRI is essential alongside CT. Ultrasound may be suitable for simple fractures in acute care. AI-based tools and radiomics are used as adjuncts rather than replacements, helping to interpret established imaging methods more effectively.

Q: What areas of research are likely to shape the next stage of development?

A: Ongoing work is focusing on further dose reduction, improved image quality at low exposure levels, and wider evaluation of photon-counting CT in routine sinonasal imaging. In MRI, researchers are exploring more sensitive ways to assess olfactory network changes and inflammatory activity. AI and radiomics research is moving towards larger, multi-centre validation and integration with clinical data to support outcome prediction. Surgical innovation is likely to concentrate on more seamless fusion of imaging, navigation and operative visualisation.

Q: What is the overall direction of travel in nasal and sinus imaging?

A: The field is moving towards imaging that is safer, more detailed and more closely aligned with personalised care. Radiation exposure is falling, soft-tissue assessment is improving, and image interpretation is becoming more quantitative. Imaging is no longer an isolated diagnostic snapshot; it increasingly underpins treatment selection, predicts prognosis and guides surgery in real time.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for general information and educational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, clinical guidance, or a substitute for consultation with a qualified healthcare professional. The content reflects current knowledge and research at the time of publication and may not cover all clinical scenarios or future developments in nasal and sinus imaging.

Readers should not use the information presented to diagnose or manage their own health conditions. Decisions about investigation, treatment, or surgery must always be made in discussion with an appropriately trained clinician who can consider individual circumstances, medical history, and local policies or resources.

Open MedScience and the authors make no representations or warranties regarding the accuracy, applicability, or suitability of the material for any particular purpose and accept no responsibility for any loss, injury, or damage arising from reliance on the content.

home » blog » medical imaging modalities »