Medical ultrasound is an imaging technique that uses high-frequency sound waves to produce real-time images of internal body structures. It is widely used because it does not involve ionising radiation, can be performed at the bedside, and provides immediate visual information that supports diagnosis, monitoring, and guidance during procedures. Understanding the fundamentals of medical ultrasound requires an appreciation of the underlying physics, how images are formed, how equipment works, and why ultrasound behaves differently in various tissues.

The basic principle of ultrasound imaging

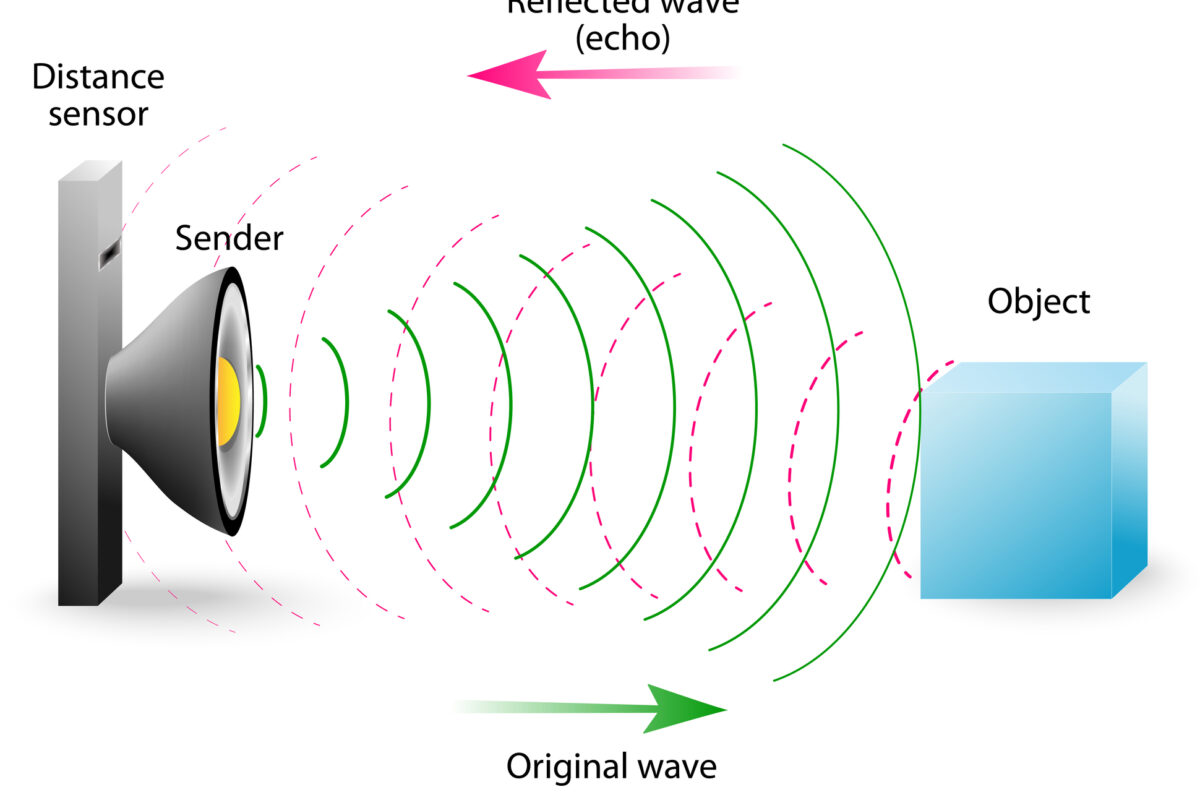

Medical ultrasound works by transmitting sound waves into the body and analysing the echoes that return. These sound waves are above the range of human hearing, typically between 2 and 15 megahertz. When the sound encounters boundaries between tissues with different physical properties, part of the wave is reflected back towards the probe, while the rest continues deeper into the body.

The ultrasound system measures the time it takes for these echoes to return and uses this information to calculate the depth of the reflecting structure. By repeating this process thousands of times per second across many adjacent lines, the system constructs a two-dimensional image of internal anatomy in real time.

This simple concept underpins all diagnostic ultrasound applications, from abdominal scanning to cardiac imaging and vascular assessment.

Sound waves and their key properties

To understand ultrasound imaging, it is essential to understand the basic properties of sound waves. Sound is a mechanical wave that requires a medium, such as tissue or fluid, to propagate. Unlike electromagnetic waves, sound cannot travel through a vacuum.

Three properties of sound are particularly important in ultrasound: frequency, wavelength, and velocity. Frequency is the number of cycles of a wave per second and is measured in hertz. Medical ultrasound uses much higher frequencies than audible sound, which allows for finer spatial resolution.

Wavelength is the distance between successive peaks of the sound wave. Higher frequencies have shorter wavelengths, which improves the ability to resolve small structures. However, higher-frequency sound is also absorbed more rapidly by tissue, limiting penetration depth.

Velocity is the speed at which sound travels through a medium. In most soft tissues, sound travels at approximately 1540 metres per second. Ultrasound systems assume this average value when calculating distances, which is why variations in tissue composition can affect image accuracy.

The role of acoustic impedance

Acoustic impedance describes how much resistance a tissue offers to the passage of sound. It depends on both tissue density and sound velocity within that tissue. When sound encounters a boundary between tissues with different acoustic impedances, some of the sound is reflected.

Large differences in acoustic impedance produce strong echoes. This explains why interfaces such as soft tissue and bone, or soft tissue and air, appear very bright on ultrasound images and often prevent visualisation of deeper structures. Smaller impedance differences, such as those between adjacent soft tissues, produce weaker echoes that contribute to image texture.

Understanding acoustic impedance helps explain common scanning challenges, such as acoustic shadowing behind bone or gas and the need for coupling gel to remove air between the probe and the skin.

Ultrasound transducers and the piezoelectric effect

The ultrasound transducer, often referred to as the probe, is the key component that both generates and receives sound waves. It contains piezoelectric crystals that change shape when an electrical voltage is applied. This deformation produces sound waves that travel into the body.

When returning echoes strike the same crystals, they deform slightly and generate electrical signals. The ultrasound system then processes these signals to form an image.

Different transducers are designed for different clinical applications. Linear probes produce rectangular images and are commonly used for vascular, musculoskeletal, and superficial imaging. Curvilinear probes create a wider field of view and are used for abdominal and obstetric scans. Phased array probes are compact and allow imaging between ribs, making them suitable for cardiac studies.

Image formation and brightness mode imaging

The most common ultrasound display format is brightness mode, often called B-mode. In B-mode imaging, each echo is represented as a dot on the screen. The brightness of the dot corresponds to the strength of the returning echo, while its position reflects the depth and direction of the structure.

By assembling many lines of sight side by side, the system creates a greyscale image that represents tissue structure. Fluid-filled areas, which produce very few echoes, appear dark or black. Dense or highly reflective structures appear bright.

Image quality in B-mode depends on several factors, including frequency, focus, gain, and depth settings. Skilled operators adjust these parameters to optimise contrast and spatial detail for the region being examined.

Resolution in ultrasound imaging

Resolution describes the ability to distinguish between two separate structures. In ultrasound, resolution is considered in two main directions: axial and lateral.

Axial resolution refers to the ability to distinguish structures that lie along the direction of the sound beam. It depends primarily on pulse length, which is influenced by frequency. Higher frequencies improve axial resolution.

Lateral resolution refers to the ability to distinguish structures side by side, perpendicular to the sound beam. It depends on the beam width and focusing. Modern systems use electronic focusing to improve lateral resolution at selected depths.

There is always a balance between resolution and penetration. Higher frequencies provide better detail but reduced depth, while lower frequencies penetrate deeper but sacrifice fine detail. Selecting the appropriate probe and settings is therefore central to effective scanning.

Attenuation and artefacts

As ultrasound travels through tissue, it gradually loses energy through absorption, reflection, and scattering. This process is known as attenuation. Attenuation increases with frequency, which is another reason higher-frequency probes have limited penetration.

Attenuation can give rise to artefacts that both hinder and help image interpretation. Acoustic shadowing occurs when a strongly attenuating structure blocks sound transmission, creating a dark region behind it. Posterior acoustic enhancement occurs when sound passes easily through a low-attenuation structure, such as a cyst, making deeper tissues appear brighter.

Recognising these artefacts is an essential part of ultrasound interpretation, as they often provide diagnostic clues rather than simply representing image errors.

Doppler ultrasound and blood flow assessment

In addition to structural imaging, ultrasound can assess motion, most commonly blood flow, using the Doppler effect. When sound reflects off moving red blood cells, its frequency shifts in proportion to the velocity and direction of flow.

Colour Doppler displays flow direction and relative speed using colour overlays on the B-mode image. Spectral Doppler provides a graphical representation of flow velocity over time, allowing detailed analysis of vascular patterns.

Doppler ultrasound is widely used in cardiology, vascular medicine, and obstetrics. It enables assessment of vessel patency, flow direction, and haemodynamic changes without invasive procedures.

Safety considerations in medical ultrasound

Medical ultrasound is regarded as a safe imaging technique when used appropriately. It does not involve ionising radiation and has a long history of clinical use.

However, ultrasound deposits energy in tissues, potentially causing thermal and mechanical effects. These effects are monitored using indices displayed on the ultrasound system, such as the thermal index and mechanical index. Operators are trained to keep exposure as low as reasonably achievable while still obtaining diagnostic information.

This safety framework supports the widespread use of ultrasound across all age groups, including in pregnancy and paediatrics.

Clinical applications across medicine

The fundamentals of medical ultrasound support a wide range of clinical applications. In abdominal imaging, ultrasound assesses organs such as the liver, kidneys, and gallbladder. In obstetrics, it monitors fetal development and placental position. In cardiology, echocardiography evaluates heart structure and function in real time.

Ultrasound also plays an increasing role in emergency medicine, critical care, and interventional procedures. Point-of-care ultrasound allows clinicians to answer focused clinical questions rapidly, often at the bedside.

These applications all rely on the same physical principles, adapted through probe design, software processing, and operator expertise.

Why understanding the fundamentals matters

A solid understanding of ultrasound fundamentals improves both image quality and diagnostic accuracy. It allows clinicians and sonographers to select appropriate equipment, recognise artefacts, and interpret findings with confidence.

As ultrasound technology continues to advance, with developments such as contrast-enhanced imaging and artificial intelligence-assisted interpretation, the underlying physics remain unchanged. Mastery of these basics ensures that new tools are used effectively and safely.

Medical ultrasound is therefore not just a practical imaging method, but a discipline grounded in physics, engineering, and clinical reasoning. Appreciating its fundamentals is essential for anyone involved in diagnostic imaging or patient care.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is provided for general educational and informational purposes only. It is intended to support understanding of the fundamental principles of medical ultrasound and does not constitute medical advice, clinical guidance, diagnosis, or treatment recommendations.

While every effort has been made to ensure accuracy and clarity at the time of publication, medical imaging technology, clinical practice, and safety guidance continue to evolve. The information presented may not reflect the most current research, regulatory standards, or clinical protocols.

Readers should not rely on this article as a substitute for professional training, accredited education, or consultation with qualified healthcare professionals. Clinical decisions, imaging practices, and patient management should always be based on formal training, institutional policies, manufacturer guidance, and professional judgement.

Open MedScience accepts no responsibility for any loss, harm, or adverse outcomes arising from the use or interpretation of the information contained in this article.

home » blog » medical physics »