Robots have been part of science fiction for decades, but in hospitals and clinics, they are now very real tools that assist surgeons, support nurses, and even move through the body itself. From da Vinci surgical systems to tiny magnetic micro-robots, medical robotics has moved well beyond novelty. It is becoming a core part of how healthcare is delivered, how operations are performed, and how patients recover.

This article looks at some of the new developments in medical robotics, from operating theatres and hospital wards to laboratories and research centres, and asks what they might mean for patients and staff over the next decade.

Surgical robots: from specialist to standard

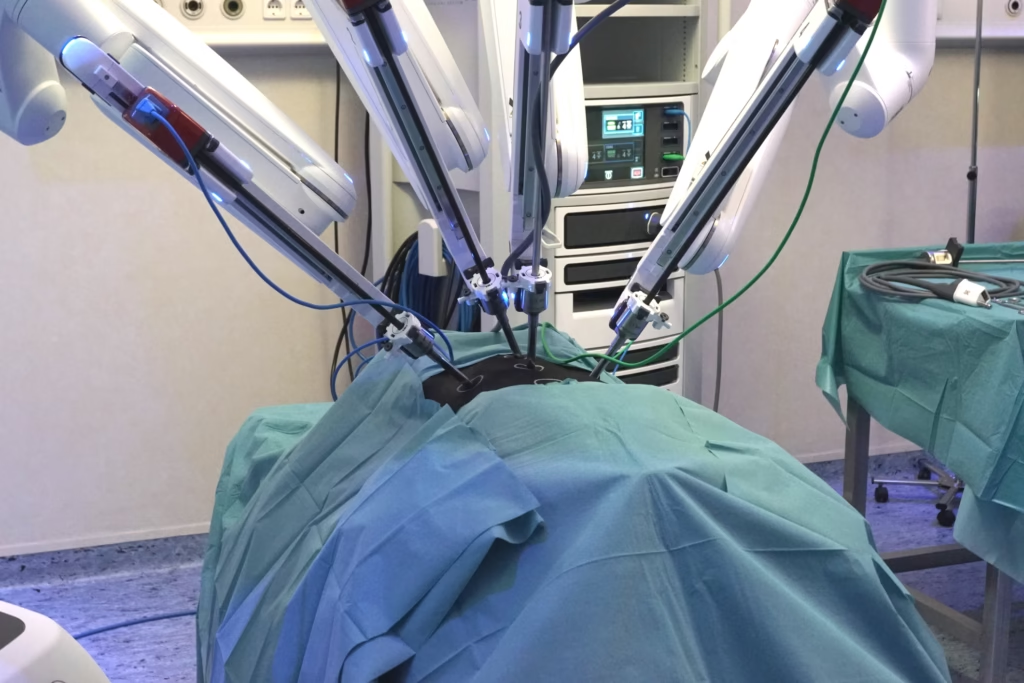

Surgical robotics is still the most visible use of robots in medicine. Systems such as Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci platform have been used for many years in urology and gynaecology. In recent years, however, the technology has become more versatile. Regulators have approved these systems for a broader range of soft-tissue procedures, including hernia repair, gallbladder surgery and some colorectal operations. That broadening of indications matters because it moves surgical robots from niche use into a more routine tool across general surgery.

New players are challenging the early systems with their own platforms. Companies such as CMR Surgical are introducing modular robotic systems in which the arms, vision tower, and surgeon console can be arranged flexibly around the patient. This modular approach gives hospitals greater flexibility to integrate robots into existing theatres rather than redesign entire rooms. It can also make it easier to share components between theatres, potentially lowering costs.

At the same time, the brains of these robots are becoming more sophisticated. Surgeons now work with high-definition 3D views, augmented by computer vision that can highlight key structures or track instruments in real time. Some systems overlay pre-operative imaging, such as CT or MRI scans, onto the surgical field. Others record large amounts of data about instrument movement, operating times and outcomes. These data can be used to give surgeons feedback on their performance or to train machine-learning models that suggest better techniques and reduce variation between operators.

Robots on the ward: helpers for staff and patients

Surgery may grab the headlines, but hospitals are also adopting robots for more everyday work. Service robots can deliver medicines and supplies, transport linen, or move specimens between wards and laboratories. In busy hospitals with staffing shortages, these tasks can consume a large amount of nursing time. Passing them to robots frees staff for activities that require human judgement and empathy.

In some countries, especially those with rapidly ageing populations such as Japan, “robot nurses” and care assistants are being piloted in long-term care facilities and hospitals. These systems do not replace nurses, but they can help with lifting, positioning or transferring patients, reducing the risk of injury for both staff and patients. Social robots with friendly faces and voices are being tested as companions for people with dementia or those with long hospital stays, providing conversation, reminders, and simple cognitive exercises.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated interest in using robots to reduce staff exposure to infectious diseases. Disinfection robots that move through wards emitting ultraviolet light, and telepresence robots that let clinicians review patients from outside isolation rooms, are now familiar in some hospitals. For infection control teams, robots offer a consistent way to apply cleaning protocols in environments where manual cleaning can vary from person to person.

Micro and nano robots inside the body

Some of the most exciting developments are happening at very small scales. Research groups around the world are designing micro-robots measured in millimetres, or even micrometres, that can travel through blood vessels or other internal pathways. Many of these devices are controlled using external magnetic fields, ultrasound or light. By adjusting the field, clinicians can steer the robot to a target area without large incisions.

The aim is to use these miniature machines for highly targeted procedures. One possible application is local drug delivery, in which a micro-robot carries a drug payload and releases it exactly where it is needed, such as inside a tumour. Another concept is micro-robots equipped with tiny cutting or ablating tools, capable of removing a blood clot or performing microscopic repairs that are difficult or impossible with current catheters.

At an even smaller scale, researchers are experimenting with nano-robots and swarms of particles that move collectively like schools of fish. Rather than controlling a single device, clinicians could influence the group as a whole to focus on a single area or to perform tasks such as breaking up plaque in arteries. These technologies are still at an early experimental stage, but they hint at a future in which surgery may involve guiding swarms rather than manual instrument manipulation.

Soft robots: machines that move like tissue

Traditional robots are usually built from rigid metals and plastics. That design works well on the factory floor, but it is less ideal for interacting with soft, delicate anatomy. Soft robotics takes a different approach, using flexible materials and structures that bend and stretch more like muscle or skin.

In medicine, soft robots are being used to create new types of catheters, endoscopes and surgical grippers. A soft robotic gripper may wrap gently around tissue rather than pinching it at a few points, reducing pressure and potential damage. Soft robotic sleeves can be placed around the heart to assist pumping in cases of heart failure, squeezing in synchrony with each heartbeat. In gastrointestinal endoscopy, soft robotic segments can help a device snake through the bowel with less discomfort.

Soft exoskeletons are also under development for rehabilitation. These wearable devices use inflatable bladders or flexible actuators instead of rigid frames, which makes them lighter and more comfortable than earlier exoskeletons.

Rehabilitation and assistive robotics

Beyond surgery and diagnostics, robots are increasingly playing a role in rehabilitation and long-term care. Robotic therapy systems for upper and lower limbs can guide a patient’s movements through repeated exercises while measuring force, range of motion and progress. Because the robot can deliver the same movement pattern thousands of times without fatigue, it complements the skills of physiotherapists and occupational therapists, who can focus on tailoring programmes and motivating patients.

For people living with disabilities, assistive robots offer new levels of independence. Wheelchairs with robotic arms can help users reach objects, open doors, or perform basic household tasks. Wearable exoskeletons support walking and standing, offering physical and psychological benefits to people with limited mobility. As control interfaces improve, including brain-computer interfaces and better voice recognition, these systems are becoming easier to use for people with severe motor impairments.

Artificial intelligence and the “intelligent” robot

The rise of artificial intelligence in medicine is closely linked with robotics. Many modern medical robots incorporate AI modules for perception, decision support and workflow optimisation. In the operating theatre, AI can help recognise anatomical structures, suggest safe cutting planes or alert the surgeon if they are approaching critical vessels or nerves. Rather than acting autonomously, the system works as a co-pilot, providing guidance while the human remains in control.

In logistics, AI algorithms help schedule robots’ movements through a hospital so they do not block corridors or overload lifts at busy times. For social and companion robots, natural language processing enables more fluid interaction with patients and staff. Machine learning models also underpin predictive maintenance, flagging when a robot is likely to fail so that engineers can service it between clinical sessions.

Regulation, safety and trust

As robots become more embedded in medicine, questions of regulation and ethics come to the foreground. Regulators in the UK and elsewhere are developing frameworks for AI-enabled devices and robotic systems. These frameworks have to balance patient safety with the need to encourage innovation, an ongoing challenge as technology evolves faster than traditional approval processes.

Transparency is critical for building trust. Clinicians and patients need to understand what a robot is doing, what data it is using and how decisions are made. Research into explainable AI, robust validation and post-market surveillance will therefore remain central to future development.

There is also an ethical dimension around workforce impact. Robots can relieve some of the burden on overstretched staff. However, healthcare systems must still invest in training, redeployment and support so that professionals see robots as partners rather than threats.

What this means for the future of care

Taken together, these developments show robots moving from specialist tools to everyday collaborators in healthcare. In operating theatres, they are extending the possibilities of minimally invasive surgery and delivering more consistent performance. Onwards, in community settings, they are taking on repetitive tasks, supporting rehabilitation, and helping people live more independently. In research laboratories, tiny robots and soft machines hint at new approaches to diagnosis and treatment inside the body.

For patients, the promise is care that is safer, more precise and more personalised. For clinicians and carers, well-designed robots can remove some of the physical strain and cognitive load that contribute to burnout. The challenge for healthcare leaders is to integrate robotics thoughtfully, ensuring that benefits are shared fairly and that human connection remains at the centre of medicine.

The next decade is likely to bring even greater convergence between robotics, imaging, data science and pharmacology. Micro-robots guided by real-time imaging may deliver drugs to exactly the right cells. Soft exosuits may blend into everyday clothing. Surgical robots may be linked to digital twins of individual patients, allowing surgeons to rehearse complex procedures in simulation before entering the theatre. As these possibilities move from research to practice, one constant will remain: the need to keep patient welfare, dignity and autonomy as the guiding principles for every new robot introduced into medicine.

Disclaimer

This article is provided for general information and education only. It is not intended to offer medical advice, clinical guidance, or professional recommendations, and it should not be used as a substitute for consultation with a qualified healthcare professional. Readers should always seek advice from an appropriate clinician regarding diagnosis, treatment decisions, or the use of medical devices and robotic systems in healthcare settings.

The technologies, organisations, products, and research developments mentioned are included for context and discussion. Their inclusion does not constitute endorsement, approval, or certification by Open MedScience, and no guarantee is given regarding performance, safety, regulatory status, or suitability for any specific application. Robotics in medicine is an evolving field, and information may change after the date of publication.

Open MedScience does not accept responsibility or liability for any loss, harm, or consequences arising from reliance on the material in this article. Any regulatory, commercial, or clinical decisions should be based on independent verification, expert advice, and applicable local laws and guidance.

You are here: home » diagnostic medical imaging blog »