In recent years, the idea of a “robotic doctor” has moved from science fiction to clinical reality: robotic and AI-assisted systems are increasingly used in operating theatres and procedural suites, and their capabilities are expanding rapidly. The article below outlines key trends, significant advances, implications and what lies ahead for these technologies.

The current state of robotic-assisted intervention

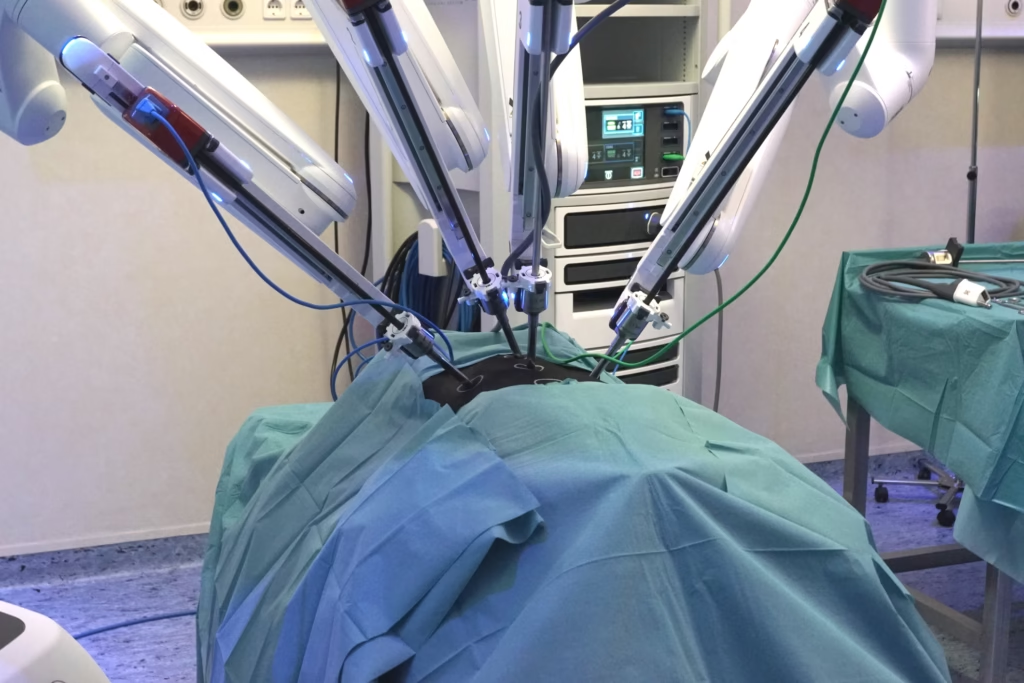

Robotic systems in surgery have been well established for some time (for example, the da Vinci Surgical System), but what is changing is how widely they are applied, the level of intelligence they incorporate, and how accessible they become. Recent reports note that robotic-assisted interventions are showing tangible benefits: improved precision, shorter hospital stays, and reduced surgeon fatigue. For example, a review found that robotic surgery is associated with fewer readmissions and shorter lengths of stay compared with open surgery.

Moreover, markets are expanding rapidly: one report projects that the global surgical robotics market will rise from around US $9 billion in 2024 to significantly higher levels by the end of the decade.

In practical terms, hospitals are increasingly adopting these tools, not just in large academic centres but increasingly in smaller or community hospitals, as cost, training and technology-adoption barriers begin to shift.

Advances in autonomy, AI and integration

One central strand of development is the move from purely manually controlled robotic arms to systems that incorporate greater automation, AI guidance, imaging integration, and sensory feedback. For instance, recent academic work reports on “autonomous dissection” in gall bladder removal procedures (cholecystectomy), where a robotic system using real-time tissue segmentation and tool-path planning executes part of the procedure with limited human input.

In addition, improved design of robotic arms with more degrees of freedom, improved ergonomics and tremor mitigation are being reported.

These efforts aim both to improve surgical precision (for example, during tumour resection and implant placement) and to reduce surgeon fatigue, error, and variability. For example, a review found that AI-assisted robotic surgery resulted in fewer intraoperative complications and shorter operative time than manual approaches.

Integration with imaging is also increasing: by combining intra-operative imaging (ultrasound, CT, fluoroscopy) with robotic tool guidance, the system can assist in navigation, making the robotic-assisted intervention more informed and less reliant on manual judgement alone.

Expanding access: location, procedure-type and cost

Another key development is the broadening of access. There are three intertwined dimensions: geography (remote/underserved sites), procedure types (more specialties), and cost/affordability models.

On the geography front, for example, the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Society of Robotic Surgery (SRS) signed a memorandum of understanding in August 2025 to promote telesurgery and virtual care in underserved regions. This explicitly targets equity of access for robotic-assisted surgery globally.

In terms of procedure types, robotic systems are moving beyond urology and gynaecology (where they have had the greatest uptake) into general surgery, orthopaedics, thoracic surgery, neurosurgery, and beyond. One market analysis noted that while urology and gynaecology remain major domains, general surgery and orthopaedics are increasingly targeted.

Finally, cost models are changing: historically, a barrier has been the high capital cost of robotic systems (millions of dollars) plus training and maintenance. Reports now suggest that, as costs fall, hospitals are adopting modular or “smaller” robotic platforms or subscription/usage models rather than outright purchase.

Together, this means more hospitals, more patients, and more procedure types will be able to access robotic-assisted interventions.

Minimally invasive and “single-port” systems

A further trend is pushing invasiveness down still further. Robotic platforms are being developed to operate through single small incisions (single-port surgery) or via even less invasive access. The idea is that by reducing trauma, bleeding, recovery time, and hospital stay, patient outcomes improve and costs are reduced. One article noted that the next generation of systems will incorporate more automation, analytics, and real-time feedback to support minimally invasive tasks.

In practice, this means robotic tools that can navigate narrower spaces, provide finer instrument articulation, integrate real-time imaging/feedback, and adapt dynamically as tissue shifts. On the surgeon’s side, ergonomic improvements (less fatigue, improved vision, better tool control) further enhance outcomes.

Why this matters (especially for imaging and interventional fields)

From your background in imaging and intervention (e.g., PET chemistry, medical imaging labs), these developments are especially relevant for a few reasons:

- Enhanced integration with imaging modalities: Integrating robotic arms with live imaging (fluoroscopy, ultrasound, CT/MR fusion) enables interventions to be increasingly automated and guided. For example, a robotic intervention for radiopharmaceutical delivery or image-guided ablation could become more efficient and accurate.

- Precision and workflow improvements: Reduced variability, improved precision, and reduced physical burden on clinicians can benefit imaging-guided interventions (which often demand high precision). The surgical robot becomes a tool that makes “imaging + intervention” more seamless.

- Access and scalability: As robotic systems become more affordable and accessible, imaging-based interventional centres (including small ones) may adopt these tools rather than relying solely on large tertiary hospitals. This could affect how you think about lab workflows, equipment purchasing, and even staffing/training.

- Regulatory, training, safety, and data implications: With increased robot-imaging integration come data management, image registration, motion compensation, security, licensing of robotic-imaging workflows, and staff training. Given your leadership role and experience in imaging labs, these are strategic considerations.

Key challenges still ahead

Even with strong momentum, there are several hurdles to the full realisation of a “robotic doctor” future:

- Cost and economics: Many hospitals still struggle with the upfront costs of robotic systems, training, maintenance, and workflow changes. Adoption remains uneven.

- Training and credentialing: Robotic systems change workflow and require surgeon training, team adaptation, new credentialing and possibly new staffing models. Without sufficient training, errors may increase or systems may underperform.

- Regulatory, ethical and data issues: As systems incorporate AI and autonomous features, questions of responsibility, safety, error liability, patient consent and data privacy are critical. For example, autonomous dissection systems raise questions about surgeon oversight and liability.

- Workflow integration and clinical evidence: In many new systems, clinical evidence across specialities is still emerging. Hospitals may hesitate until robust trials demonstrate cost-effectiveness, outcomes benefit, and workflow fit.

- Accessibility and equity: Although access is improving, there remains a risk that advanced robotics will deepen disparities if only large or well-funded centres deploy them. Initiatives such as the WHO-SRS partnership seek to mitigate this.

What’s next: the near-term horizon

Given current trajectories, the next few years are likely to bring:

- More autonomous surgical/procedural modules: Systems that can autonomously perform specific steps of operations under supervision (e.g., tissue dissection, suturing) will become more common. The autonomous cholecystectomy study is one example of this direction.

- Greater imaging-robotics fusion: The combination of high-resolution imaging (real-time intra-operative CT/ultrasound/fusion) with robotic manipulation means interventions will become quicker, more accurate, and less error-prone.

- Broader procedural types and smaller centres: Institutions outside large academic centres will increasingly adopt robotic-assisted platforms for a variety of surgeries, including orthopaedic, thoracic, general, and interventional radiology procedures.

- Scalable cost models and subscriptions: Rather than simply purchasing a multimillion-dollar system and amortising it over years, hospitals may adopt “robotics-as-a-service”, per-procedure billing, modular add-ons or leasing models. This will enable wider access.

- Remote and telesurgery expansion: Especially where specialist surgeons are in short supply, remote robotic interventions will grow. The WHO-SRS initiative is a step in that direction. Telesurgery will gradually shift from demonstrations to routine use in selected contexts.

- Haptic feedback and immersive surgeon interfaces: As ergonomics and interface design improve (for example, through a better sense of “touch” via haptic feedback), the gap between the surgeon and the robot will shrink. Surgeons will feel more like “in the body” via robotic instrument controls.

- Data-driven robotics and real-time analytics: Robotic systems will increasingly leverage data (preoperative imaging, intraoperative sensors, postoperative outcomes) to learn, adapt, and improve. Real‐time analytics may guide robotic tool trajectories, risk detection, tissue identification and intra-operative decision support.

What this means for you

Considering your background in imaging, medical physics, radiolabelling and directing a team in a PET/imaging-chemistry environment, here are some specific reflections:

- As robotics becomes more integrated with imaging modalities, your lab and your team may find opportunities for collaboration (e.g., robotic intervention guided by PET/CT, combined imaging-robotic workflows).

- When evaluating investments in new equipment or collaborations, consider the emerging trend of robotic imaging integration, not just standalone robotics.

- For training and team deployment, as robotics spreads into interventional imaging labs, ensuring your team has the right multidisciplinary skills (robotics, imaging, procedural workflows, safety/data) will be a differentiator.

- In your leadership role, you may wish to explore how your imaging group can support robotic programs (for example, image registration, dosimetry, PET tracer delivery guidance) or how procedural robotics may impact workflow and staffing.

- From a strategic viewpoint, changes in cost models, accessibility and scope of robotic systems may influence how you advocate for technology in your centre (e.g., smaller hospitals, shared platforms, outpatient interventional centres).

- Finally, keep an eye on regulatory, safety, and ethical issues: as robotics becomes more autonomous, issues such as credentialing, oversight, data governance, and training will become increasingly salient. As someone managing PET chemists and overseeing high-value lab operations, your awareness of cross-disciplinary standards (robotics, imaging, and intervention) will be useful.

Conclusion

The “robotic doctor” concept is no longer purely hypothetical. Robotic and AI-assisted systems are now established, expanding and becoming more advanced, ranging from enhanced imaging integration, procedural automation, remote/telesurgery, broader access, lower-cost models, and new specialities. For imaging and interventional leaders, these developments offer significant opportunities and implications for workflow, team composition, training, technology investment, and strategic planning.

While challenges remain — cost, training, regulation, evidence, equity — the momentum is strong. Over the coming years, we are likely to see robotic-assisted interventions become the norm rather than the exception in many surgical and interventional fields. Embracing and preparing for this shift will help you and your team remain at the forefront of medical imaging and therapy innovation.

Disclaimer

This article is provided for general information and educational purposes only. It does not offer medical advice, clinical guidance, or recommendations for patient care. Any technologies, systems, or procedures mentioned should be evaluated by qualified healthcare professionals and considered within the context of local regulations, training requirements, and institutional policies. Open MedScience does not endorse specific products or manufacturers, and no clinical decisions should be made based solely on the content of this article. Readers should consult appropriate medical or regulatory authorities for professional advice.