Summary: Diabetes is a group of metabolic disorders characterised by elevated blood glucose levels stemming from challenges with insulin production, insulin action, or both. These complications can lead to a host of short-term and long-term health issues if not appropriately managed. Current estimates show that millions of individuals around the world live with diabetes, and the prevalence is increasing due to factors such as changes in diet, levels of physical activity, and an ageing population.

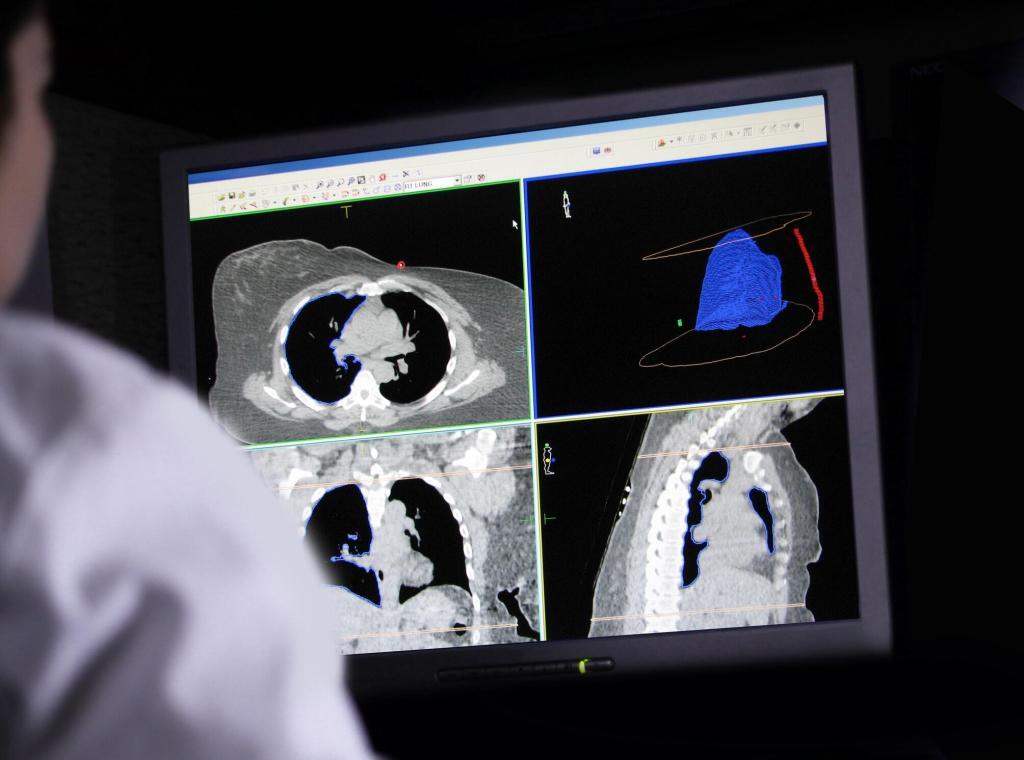

Medical imaging has become an essential tool in the management and study of diabetes, providing clear visualisations of structures such as the pancreas, liver, heart, and vascular system—imaging modalities aid in diagnosing diabetic complications, planning interventions, and monitoring treatment efficacy. Traditional imaging methods, such as ultrasound and computed tomography (CT), help doctors investigate internal anatomy and identify signs of disease progression, while advanced techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) enable a more detailed examination of tissue functionality.

In this article, we will outline the major types of diabetes—Type 1, Type 2, gestational diabetes, and other variants—and then discuss in detail how medical imaging contributes to improved detection and care. By integrating careful clinical management with imaging insights, healthcare professionals can offer more personalised treatment, enabling patients to manage their condition better. Ultimately, these imaging approaches can help enhance patient outcomes and mitigate the risk of severe diabetes-related complications through timely and precise intervention.

Keywords: Type 1 diabetes; Type 2 diabetes; Gestational diabetes; Medical imaging; Pancreas; Blood glucose.

Introduction to Diabetes

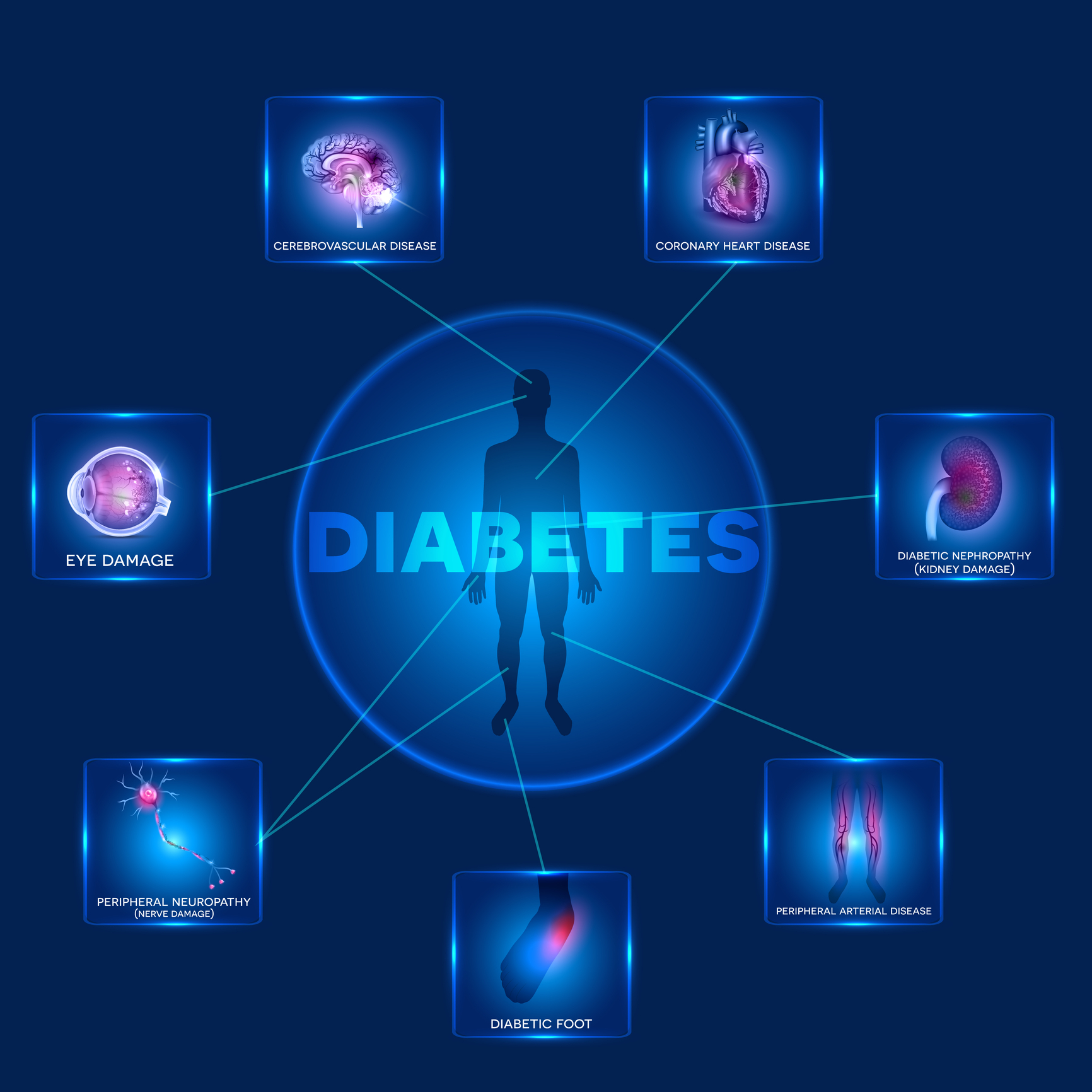

Diabetes is a chronic condition in which the body struggles to regulate blood glucose, leading to profound health implications when left untreated. In a healthy person, insulin—a hormone produced in the pancreas—helps glucose enter cells to be used for energy. When the body does not produce enough insulin or cannot properly use the insulin it produces, glucose accumulates in the bloodstream. Over time, elevated blood glucose can damage multiple organs, including the kidneys, heart, and eyes, increasing the risk of complications such as heart disease, blindness, and nerve damage.

Awareness of diabetes continues to grow, as do efforts to improve our understanding of this condition. Alongside pharmaceutical and lifestyle interventions, medical imaging plays a crucial role in detection, disease monitoring, and treatment planning. Through imaging technologies, clinicians can assess organ function, detect complications at an earlier stage, and tailor management strategies to each patient’s unique needs.

Understanding Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus encompasses several conditions marked by prolonged high blood sugar levels. These conditions generally arise from dysfunctions related to insulin secretion or action. Though the most frequently discussed forms are Type 1 and Type 2, there are additional variants such as gestational diabetes and rarer, genetically driven types.

One of the most critical elements of diabetes care is early detection, as prolonged hyperglycaemia can silently cause damage to blood vessels and nerves. Patients may initially experience symptoms like frequent urination, increased thirst, sudden weight loss, fatigue, and blurred vision. However, individuals might not notice these warning signs in some instances until more advanced complications emerge. This is one reason why routine screening, especially for those with risk factors like obesity or family history, is highly recommended.

Once diabetes is diagnosed, the challenge lies in maintaining controlled blood glucose levels. Various management strategies exist, including insulin therapy, oral medications, adjustments to dietary patterns, and increased physical activity. These interventions aim to stabilise blood sugar and reduce the risk of complications. Technology has also advanced considerably in recent years, offering blood glucose monitors, continuous glucose monitoring systems, and smart insulin pumps that give patients a more precise way to manage their condition.

In modern medical practice, imaging contributes significantly to understanding the causes and progression of diabetes. Imaging techniques enable doctors to examine the pancreas for structural abnormalities, assess cardiovascular health, and detect early signs of complications in organs such as the kidneys and liver. By correlating imaging findings with biochemical markers, clinicians can more accurately assess a patient’s diabetic status. Data integration leads to a more accurate approach to prevention, early intervention, and ongoing care.

Type 1 Diabetes

Type 1 diabetes, sometimes referred to as insulin-dependent diabetes, is primarily an autoimmune disorder in which the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks and destroys the pancreas’s insulin-producing beta cells. Because of this destruction, individuals with Type 1 diabetes produce little to no insulin. It commonly manifests in childhood or early adulthood but can occur at any age.

Cause and Risk Factors: Although the exact cause remains under investigation, certain genetic and environmental factors are thought to contribute to the autoimmune response. Family history can increase susceptibility; particular genes might make some individuals more prone to autoimmune disorders. Environmental triggers like viral infections may also initiate or speed up the autoimmune process.

Symptoms and Diagnosis: Due to the lack of insulin, glucose cannot enter cells properly, causing a rapid rise in blood sugar. Symptoms often develop swiftly and include excessive thirst, frequent urination, significant fatigue, and unexplained weight loss. Diagnosis involves blood tests such as measuring fasting blood glucose, random blood glucose, and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Identifying certain autoantibodies (for example, islet cell antibodies) can further support a Type 1 diagnosis.

Treatment and Management: Individuals diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes typically require daily insulin injections or an insulin pump to regulate their blood glucose. In addition, close self-monitoring of blood sugar levels is vital for adjusting insulin doses, meals, and physical activity. Education on carbohydrate counting and balanced nutrition is equally important. With rigorous attention to insulin administration, diet, and exercise, many people with Type 1 diabetes can lead healthy and productive lives. However, they are still at risk of complications if their blood glucose levels remain uncontrolled.

Medical Imaging Relevance: Medical imaging can help in understanding changes in the pancreas, providing information on residual beta cell mass. Although direct imaging of the islets remains a challenge, certain advanced imaging techniques, including MRI, are being investigated for their potential to visualise and track autoimmune activity. Moreover, imaging can be used to assess the general state of abdominal organs and vascular structures, allowing early detection of issues like diabetic nephropathy or fatty liver disease that might arise over time.

Type 2 Diabetes

Type 2 diabetes is the most prevalent form of diabetes and is characterised by insulin resistance combined with gradual insulin production dysfunction. In this condition, the body’s cells do not respond to insulin as efficiently as they should. Over time, the pancreas struggles to keep up with insulin demands, resulting in higher blood glucose levels. Type 2 diabetes typically develops in adulthood, but it is increasingly being diagnosed in younger populations due to lifestyle factors.

Cause and Risk Factors: The chief risk factors for Type 2 diabetes include obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, poor dietary habits, and a family history of diabetes. Excess body fat, particularly around the abdomen, is a significant contributor to insulin resistance. Genetic predisposition also plays a role; when combined with unhealthy lifestyle choices, the likelihood of developing Type 2 diabetes can rise significantly.

Symptoms and Diagnosis: Symptoms often develop gradually and can be subtle in the early stages. Fatigue, frequent urination, thirst, and blurred vision may be overlooked or attributed to other causes. Consequently, Type 2 diabetes may remain undiagnosed for years. Routine check-ups, which assess blood glucose levels and HbA1c, play an important part in recognising the problem before complications set in. Screening is strongly advised for individuals who have obesity, a family history of diabetes, or other associated risk factors.

Treatment and Management: Interventions often begin with lifestyle modifications: adopting a more balanced diet, increasing physical activity, and aiming for weight reduction. Medications—such as metformin—are commonly prescribed when lifestyle changes alone are insufficient for controlling blood glucose. Over time, some individuals may require additional oral medications or insulin injections. Regular monitoring of blood sugar is crucial for measuring progress and adjusting treatments accordingly.

Medical Imaging Relevance: Imaging supports evaluating coexisting conditions frequently accompanying Type 2 diabetes, such as fatty liver disease or atherosclerosis. Ultrasound can be used to measure liver fat and assess blood flow in peripheral arteries, while CT or MRI might help reveal complications affecting abdominal organs. By providing these insights, imaging can alert healthcare professionals to potential risks and guide treatment decisions.

Gestational Diabetes

Gestational diabetes (GDM) is diagnosed when a pregnant woman who does not have pre-existing diabetes experiences elevated blood glucose levels during pregnancy. This condition usually emerges in the second or third trimester and typically resolves after childbirth. However, GDM is a warning sign that the mother may be at increased risk of developing Type 2 diabetes later in life.

Cause and Risk Factors: Hormonal changes during pregnancy can interfere with insulin action, increasing the mother’s insulin needs. If her body cannot meet these increased demands, blood glucose levels rise. Being overweight, having a family history of Type 2 diabetes, or belonging to certain ethnic groups can heighten the risk. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is another significant risk factor.

Symptoms and Diagnosis: Many women with GDM experience no apparent symptoms, which is why screening protocols are crucial. The standard screening involves an oral glucose tolerance test, where a woman’s blood glucose levels are measured before and after consuming a glucose-rich drink. Elevated results confirm a diagnosis of gestational diabetes.

Treatment and Management: Management typically focuses on dietary modifications, monitoring blood glucose, and engaging in gentle exercises appropriate for pregnancy. Insulin therapy may be prescribed if these measures do not adequately control blood sugar. Regular prenatal check-ups are key, as poorly managed gestational diabetes can contribute to complications such as larger-than-average babies, leading to delivery challenges.

Medical Imaging Relevance: Ultrasound examinations are routine during pregnancy to assess the baby’s growth and amniotic fluid levels. In the case of gestational diabetes, these ultrasounds become even more crucial to detect signs of macrosomia (excess foetal growth) and to monitor placental function. Though gestational diabetes tends to resolve after delivery, imaging can also assist in evaluating any lingering health issues for the mother, encouraging timely interventions if required.

Other Forms of Diabetes

Beyond the three main categories—Type 1, Type 2, and gestational diabetes—some rarer forms also exist. For example, certain monogenic diabetes variants are caused by single-gene mutations affecting insulin production or action. Maturity-Onset Diabetes of the Young (MODY) is one such condition, presenting with mild hyperglycaemia in adolescence or early adulthood. Neonatal diabetes is another rare variant, often apparent in infants before six months of age.

Pancreatitis or damage to the pancreas from conditions such as cystic fibrosis may lead to “secondary diabetes,” in which the pancreas is unable to produce sufficient insulin. Endocrine disorders, including Cushing’s syndrome and acromegaly, can also cause abnormal glucose metabolism. In such instances, managing the underlying condition is key to controlling the secondary diabetic state.

Medical imaging is crucial in identifying structural abnormalities, guiding surgical decisions, and planning treatment. Scans can provide important data that aligns with laboratory findings by offering a window into pancreatic anatomy or any relevant tumours and lesions. Although these forms of diabetes are less common, they underscore the complexity of glucose regulation in the body and the significance of personalised, context-specific care.

The Role of Medical Imaging in Diabetes

Pancreatic Imaging

One of the primary organs of interest in diabetes is the pancreas. Although most forms of diabetes reflect a complex interplay of factors involving hormone regulation and insulin action, the pancreas is central because it produces insulin. Several imaging modalities are useful in examining the structure and potential damage to the pancreas:

- Ultrasound: A widely available, cost-effective option that can show overall pancreatic anatomy and detect major lesions or cysts. In some cases, endoscopic ultrasound provides more detailed images of the pancreas, aiding in the identification of inflammation, fibrotic changes, or nodules.

- Computed Tomography (CT): Offers cross-sectional images that can reveal abnormalities in the pancreas, such as calcifications or masses. Contrast-enhanced CT scans also assist in assessing blood flow and vascular involvement.

- Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI): Useful for soft tissue contrast, MRI can provide a more detailed look at the pancreatic structure without ionising radiation. Specialised MRI sequences (for example, MR elastography) can help gauge tissue integrity, while MR spectroscopy may offer insights into metabolic processes within the organ.

- Positron Emission Tomography (PET): Often paired with CT or MRI, PET imaging can reveal metabolic activity, helpful in cases where autoimmune processes or inflammation might be suspected.

Though direct imaging of beta cells is not yet routine clinical practice, research is underway. Investigations aim to develop tracers or techniques that can better visualise and monitor beta cell mass, which could transform how we track the progression of diabetes and the impact of treatments.

Cardiac and Vascular Imaging

People with diabetes, especially Type 2, are at greater risk of cardiovascular disease. Continuous exposure to high blood sugar can injure the endothelium (the lining of blood vessels), encouraging plaque formation. As a result, detecting cardiovascular complications as early as possible is key to preventing severe outcomes like heart attacks or strokes.

- Echocardiography: This ultrasound-based technique helps evaluate heart function and structure in a non-invasive way. It can detect alterations in cardiac function, valve problems, or early signs of heart failure.

- Coronary CT Angiography (CCTA) Provides detailed images of the coronary arteries and helps detect coronary artery disease. By identifying plaque build-up, CCTA can evaluate the extent of atherosclerosis and guide possible interventions.

- Ankle-Brachial Index (ABI) and Peripheral Ultrasound: Although not imaging in the traditional sense, these tests assess blood flow in peripheral arteries. Ultrasound of the peripheral vessels can identify early vascular disease that might become limb-threatening if ignored.

- Cardiac MRI: Offers a refined method to assess heart structure and function, along with myocardial perfusion. Cardiac MRI can clarify the presence and severity of conditions such as cardiomyopathies, ischaemic heart disease, or myocardial fibrosis.

Renal Imaging

Kidney disease is a prominent complication of long-standing diabetes. Chronic hyperglycaemia can harm the delicate kidney filtering units (nephrons). Early detection of diabetic nephropathy is essential in preventing end-stage renal disease, which may require dialysis or kidney transplantation.

- Ultrasound: The first-line imaging approach for assessing kidney size and ruling out obstructions. It is non-invasive, safe, and widely accessible. If the kidneys are significantly shrunken, this could point to chronic kidney damage.

- CT and MRI: These modalities offer more detailed anatomical information. When combined with contrast, CT or MRI can reveal how blood flows through the kidneys and identify any structural issues, such as scarring or cysts. However, contrast use must be carefully evaluated in patients with compromised kidney function.

Liver Imaging

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are increasingly common among individuals with Type 2 diabetes. Accumulation of excess fat in the liver can eventually result in liver inflammation and scarring.

- Ultrasound: Useful for detecting fatty liver; doctors may see an increase in echogenicity (the brightness on the scan), indicating fat deposits.

- MRI Proton Density Fat Fraction (MRI-PDFF): An advanced technique that accurately measures the amount of fat in the liver. This can be invaluable for both diagnosing and monitoring progression or response to therapy.

- FibroScan (Transient Elastography): While not a traditional imaging modality in the same sense as CT or MRI, it measures liver stiffness using ultrasound-based technology, which can indicate the severity of fibrosis or scarring.

Eye Imaging

Diabetic retinopathy is a major cause of blindness. High blood sugar can damage the blood vessels in the retina, and early changes may be difficult to spot without specialised imaging.

- Fundus Photography: A simple method that captures images of the back of the eye, revealing damage to retinal vessels, including microaneurysms or haemorrhages.

- Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT): Provides cross-sectional images of the retina, enabling detection of retinal swelling (macular oedema) and other subtle irregularities that may precede vision loss.

- Fluorescein Angiography: Involves injecting a fluorescent dye into a vein in the arm. A special camera then takes images of the dye as it circulates through the retinal vessels. Areas of leakage or blockage become apparent, helping guide laser therapy.

Novel and Emerging Imaging Methods

Researchers continue to explore new imaging approaches to refine the diagnosis, monitoring, and treatment of diabetes. There is ongoing interest in using high-resolution MRI to precisely quantify pancreatic fat content and investigate its correlation with insulin production and resistance. Some studies utilise advanced PET tracers to investigate inflammatory processes in the pancreas and throughout the body.

Additionally, the combination of imaging with machine learning has the potential to boost diagnostic speed and accuracy. Automated algorithms could detect subtle changes in organ images that might predict complications well before clinical symptoms manifest. Such predictive tools may eventually transform diabetes care by allowing earlier and more targeted interventions.

Importance of Imaging in Personalised Care

Medical imaging promotes a more individualised approach to managing diabetes. By offering objective data on organ health, tissue integrity, and blood flow, imaging guides the choice of therapies and the allocation of healthcare resources. In practice, this means identifying a patient at heightened risk of kidney problems early on, intensifying their treatment plan, or pinpointing early cardiovascular disease that may be slowed down or reversed with specific measures.

Furthermore, imaging can serve as a motivational tool. Sometimes, visual evidence of disease can encourage patients to adopt lifestyle changes more earnestly. For instance, a scan showing liver fat accumulation might prompt a person to modify their diet and physical activity patterns more closely.

Conclusion

Diabetes is a multifaceted condition with global implications. Its different types—Type 1, Type 2, and gestational diabetes—share the common thread of abnormal blood glucose regulation, yet they each arise from distinct causes and carry their own risks. Additional forms, such as those triggered by specific genetic mutations or secondary to other health issues, further underscore the complexity of the condition.

Fortunately, advances in medical science, from new pharmaceutical treatments to more accurate glucose monitoring devices, have improved the prognosis for many living with diabetes. Medical imaging has added a novel dimension to prevention, diagnosis, and management. By allowing doctors to detect organ damage earlier, assess the severity of complications, and gauge treatment effectiveness, imaging can facilitate a more targeted, individualised plan for each patient. Techniques such as ultrasound, CT, MRI, and emerging imaging innovations all play a significant role in a comprehensive diabetes care strategy.

Though challenges remain, continued interdisciplinary research—and patient education—can drive improvements in detection and care. In the years ahead, medical imaging and its integration with cutting-edge technologies may hold the key to even better outcomes, empowering clinicians and patients to navigate diabetes more effectively.

Disclaimer

This article is intended for informational and educational purposes only and should not be considered a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the content, Open Medscience does not guarantee its completeness or applicability to individual cases. Readers are advised to consult qualified healthcare professionals for personalised medical guidance.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any affiliated institutions or organisations. References to specific technologies or imaging methods do not imply endorsement. Open Medscience accepts no responsibility for any loss, injury, or inconvenience sustained by individuals relying on the information provided in this article.

home » blog » medicine »