Summary: This article offers a brief introduction to reading X-ray images, covering the basic physics behind X-rays, the common anatomy seen in these images, and practical advice for systematic examination. Beginning with fundamental concepts, it then explains the anatomy visible on different X-rays, provides a general step-by-step approach to reading them, and finishes with tips for avoiding common mistakes. Healthcare students, new clinicians, and curious individuals can benefit from developing a more structured approach to reading X-ray images.

Keywords: X-ray; Interpretation; Anatomy; Chest; Fracture; Imaging.

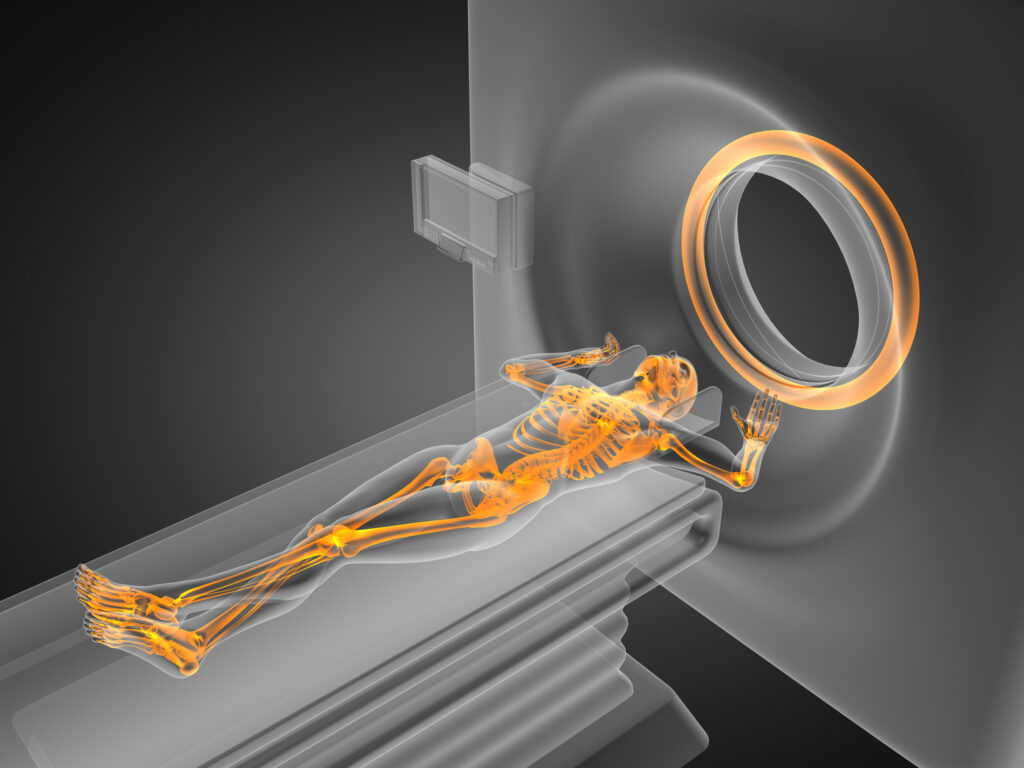

The Science Behind X-Rays

X-rays were discovered in the late 19th century by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen. Their unique ability to pass through certain materials—such as soft tissue—while absorbed by denser tissues, such as bone, makes them especially useful in medical imaging. A machine sends an X-ray beam through the body to reach a film or digital detector on the other side to create an X-ray image. Dense structures, including bones and metal implants, appear white in the resulting image because they absorb more of the beam. Softer tissues, which allow more X-ray beams to pass, create varying shades of grey. Air-filled structures like the lungs appear darker because they absorb fewer X-rays.

The intensity of this beam and how different structures absorb it form the basis of X-ray interpretation. Understanding the contrast between soft tissue and bone is necessary for a clear reading. For example, tumours or abnormal growths can sometimes be identified by changes in density. However, they can be more difficult to distinguish if they do not differ significantly from the surrounding tissues. Meanwhile, fractures are generally easier to spot because of the abrupt change in the contour of a bone.

Common Types of X-Ray Views

The type of X-ray ordered usually depends on the body region under examination and the suspected diagnosis. Below are some frequently encountered X-ray views:

Chest X-ray (CXR)

The chest X-ray is one of the most common imaging modalities. It provides essential details about the lungs, heart, and bony structures. Typical standard views are the posteroanterior (PA) and lateral projections. In certain circumstances (such as severely ill patients), an anteroposterior (AP) film may be taken with a portable X-ray machine at the bedside.

Abdominal X-Ray

Abdominal X-rays are often used to look for signs of intestinal obstruction, perforation (free air under the diaphragm), kidney stones, or foreign bodies. These are typically obtained in an AP projection, and sometimes, an erect chest X-ray is included in the series to check for free air beneath the diaphragm.

Skeletal X-Rays

A skeletal X-ray is taken when a patient is suspected of having a broken bone or if the healthcare provider wants to confirm degenerative changes, infection, or tumours in the skeletal system. Common examples include X-rays of the skull, spine, wrist, hand, knee, and foot. Each region demands careful positioning to ensure that potential fractures or other abnormalities are not missed.

Dental X-Rays

Dental X-rays are used to examine tooth structure, gum health, and the jaw. They help identify cavities, impacted teeth, and other oral issues.

Understanding the typical views you might encounter for each body part sets the stage for a more consistent approach to X-ray interpretation.

A Systematic Method for Reading X-Rays

Consistency is essential in X-ray interpretation. Following a systematic approach, each time reduces the likelihood of missing something important. Below is a structured method that can be applied generally to any X-ray:

Confirm Patient Details

Always start by checking the patient’s name, date of birth, and the X-ray date. Ensuring you have the correct patient and the correct X-ray is an obvious but critical first step.

Check the Orientation and Projection

Identify whether the X-ray is AP, PA, lateral, or another specialised view. Confirm which side of the body is right or left to avoid confusion.

Assess the Image Quality

Image quality can impact interpretation. Is the film underexposed or overexposed? Are the anatomical structures well-centred and not distorted by poor positioning? Poor image quality can mask details or create artefacts that mimic pathology.

Employ a Standard Viewing Order

Depending on the body region, adopt a sequence. For example, if you are looking at a chest X-ray, you might begin with the airways and then examine the bones, diaphragm, lungs, heart, and soft tissues in that order. This consistency ensures you do not overlook crucial regions.

Compare with Previous Studies

If available, compare the current X-ray with older images. Changes often reveal the lesion’s progression, healing, or stability.

Summarise Findings

After a thorough scan, summarise the key features. This helps consolidate and communicate your findings effectively to colleagues or the patient.

Reading a Chest X-ray

The chest X-ray is a prime example of how a systematic approach saves time and minimises mistakes. Below is one commonly taught sequence (often remembered through various mnemonics):

Assess Technical Quality

Check the rotation by inspecting whether the spinous processes align with the clavicles’ centre. Examine the inspiration level by counting the visible posterior ribs above the diaphragm; ideally, you should see around ten. Notice if the scapulae are out of the lung fields in a PA view, indicating an acceptable patient position.

Trachea and Mediastinum

Evaluate whether the trachea is midline. A shifted trachea can signify tension pneumothorax or large pleural effusion. Next, look at the mediastinal silhouette. Widening may indicate problems like an aortic aneurysm or mediastinal mass.

Heart Size and Contour

The heart should be assessed for its size relative to the thoracic cavity. Typically, the cardiac silhouette should not exceed half the thoracic diameter in a PA view. Examine contours for any unusual bulges or shapes.

Diaphragm and Costophrenic Angles

The right hemidiaphragm is often slightly higher than the left. The costophrenic angles should appear sharp where the diaphragm meets the ribs. Blunting may suggest pleural effusion.

Lung Fields

Examine the lung parenchyma for areas of increased opacity (such as consolidation in pneumonia) or hyperlucency (as in emphysema or pneumothorax). Compare left and right lungs, checking for symmetrical aeration.

Soft Tissues and Bones

Inspect the visible rib cage, clavicles, scapulae, and any part of the spine included in the view. Look for fractures, lytic lesions, or unusual calcifications. Check the soft tissues of the chest wall and neck for swelling or subcutaneous emphysema.

Other Devices or Foreign Bodies

Many patients have lines, tubes, or devices like pacemakers. Ensure they are correctly positioned and look for any complications, such as misplaced endotracheal tubes or nasogastric tubes. Foreign bodies in the chest may also be visible.

Reading a Skeletal X-Ray

When examining a skeletal X-ray (for example, the hand or wrist), an organised method helps avoid missing fractures or subtle changes:

Identify the Projection

For wrists, you may encounter PA, lateral, and oblique views. The same principle applies to other joints.

Check the Soft Tissues

Before focusing on the bone, look at soft tissue swelling or displacement. An abnormal soft tissue outline can sometimes be the first hint of a fracture, even if the fracture line is subtle.

Trace the Bone Cortex

Examine each bone border carefully from one end to the other, looking for disruptions, steps, or cracks in the cortex.

Assess Joint Spaces

Compare the spaces between bones in a joint. Loss of space or misalignment can suggest dislocation or advanced arthritis.

Bone Density

A sense of bone density (osteopenia, osteoporosis, or sclerosis) can explain chronic conditions.

Growth Plates (in children)

In paediatric X-rays, growth plates are still open. Understanding regular growth plate appearances is crucial for not mistaking them for fractures.

Summarise Any Findings

Fractures, signs of infection (such as periosteal reaction), degenerative changes, or bone tumours should be noted, with additional imaging recommended.

Practical Tips for Interpreting X-Rays

Use Adequate Lighting and the Correct Tools

Whether examining a physical film on a lightbox or using digital images on a workstation, ensure your environment is conducive to focused observation. Adjust brightness and contrast settings or use magnification where necessary.

Develop a Consistent Routine

Follow the same systematic pattern every time. Repetition helps train your eye to detect both common and subtle abnormalities.

Correlate Clinically

The clinical context in which an X-ray was taken matters. A chest X-ray ordered to check for pneumonia will warrant a focused hunt for consolidation or effusion, whereas a trauma scenario demands special attention to potential fractures or pneumothorax.

Compare Both Sides

When possible, look at the symmetry between the left and right sides, particularly in skeletal and chest X-rays. Many diseases present with unilateral changes, and noticing an asymmetry is often the first step towards identifying a problem.

Be Alert to Common Pitfalls

Normal variants, artefacts, or even overlapping structures can mimic pathology. A classic example in chest X-rays is the scapula or the nipple shadow appearing as a suspicious lesion. Additional views or other imaging modalities (CT, MRI) can be clarified if uncertain.

Seek a Second Opinion When in Doubt

Especially for those still learning, consulting a radiologist or a more experienced clinician is always advisable if something seems unclear.

Spotting and Describing Abnormalities

When you come across an abnormality on an X-ray, describing it in a standardised format helps convey what you see and your interpretation:

Location

Pinpoint the exact position of the abnormality. For instance, if you find a lesion in the lung, specify which lung, which lobe, and if it is central or peripheral.

Size and Shape

Estimate the dimensions (using known reference points or measuring tools) and comment on whether the shape is round, irregular, well-defined, or poorly defined.

Density or Opacity

Is it more radiopaque (whiter) or radiolucent (darker) compared to the surrounding tissue? This guides your differential diagnosis.

Border or Edge

Sharp, well-demarcated edges may suggest a benign process, while spiculated or irregular borders raise suspicion of malignancy.

Associated Changes

Look for any involvement of surrounding structures. For example, if you see a suspicious mass in the lung, check the associated lymph nodes or potential collapse of surrounding lung tissue.

Proper descriptive ability is essential for communicating findings clearly to other medical professionals or writing thorough reports.

Special Considerations

Paediatric X-Rays

Children’s bones differ significantly from adults as they have unfused growth plates. Bones are also more flexible, meaning fractures might not follow the typical patterns seen in adults. In chest X-rays, the thymus gland in younger children can mimic a mediastinal mass, and knowledge of normal variants in children is crucial.

Elderly Patients

Older patients may have osteopenia, degenerative changes, or previous surgical interventions (e.g., joint replacements). Metal implants can obscure views, so extra care is needed to ensure other structures are evaluated thoroughly.

Trauma Cases

Multiple injuries can be present, and stress fractures or hairline fractures might be missed if the focus is only on the most apparent broken bone. Reassessment of all visible structures is advisable.

Medical Devices

Always check the integrity and position of orthopaedic hardware, pacemaker leads, central venous catheters, or feeding tubes. Malposition can lead to complications.

Portable vs. Formal Department X-Rays

Portable X-rays in hospital wards or operating theatres often have limitations: suboptimal positioning, a lower power generator, or restricted views due to patient condition. Interpret these images carefully, recognising that they might not be as transparent as standard department X-rays.

Building Confidence and Expertise

Reading X-rays is part science, part art. Training your eyes to recognise normal anatomy is as vital as learning to identify pathology. Some strategies to enhance your skills include:

Practice Regularly

Spend time examining both normal and abnormal X-rays. Repeated exposure to many examples is the best way to learn.

Use Teaching Resources

Many online resources and textbooks illustrate classic appearances of common conditions, from pneumonia to various fractures. Studying such examples will equip you with pattern recognition skills.

Attend Teaching Sessions

Whether formal classes or informal discussions with radiologists, group sessions often provide valuable insights. They also allow for immediate correction of misconceptions.

Follow Up Cases

Review subsequent tests or definitive imaging modalities to confirm the diagnosis if you identified a suspicious abnormality in a patient. This feedback loop helps refine your clinical judgement.

Maintain a Log of Interesting Cases

Keeping a personal record of challenging or educational cases can reinforce learning points. Periodic review of these cases helps to solidify your understanding.

Conclusion

Reading an X-ray carefully requires understanding the underlying physics, recognising normal anatomy, and methodically searching for abnormalities. A thorough, stepwise approach is the key to reliable interpretation. Whether you are a medical student, a new clinician, or an interested patient, studying the fundamentals provides a foundation for spotting deviations from the norm. Pattern recognition and clinical context allow you to refine your diagnostic accuracy over time, ensuring that subtle clues do not slip unnoticed. By incorporating a consistent routine, comparing multiple views and older studies, and seeking additional imaging or advice when uncertain, you set yourself up to successfully identify various conditions.

In addition, keep in mind that an X-ray alone may not provide the full picture. Further imaging with CT, MRI, or ultrasound modalities may be required if something appears suspicious. Nonetheless, X-rays remain a first-line investigation for countless clinical presentations and remain central to medical practice worldwide.

Disclaimer

The content of this article is intended for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. While care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of the information provided, it is not a substitute for professional clinical judgement or consultation with a qualified healthcare provider. Interpretation of X-ray images should be performed by trained professionals, and medical decisions should always be based on a combination of clinical findings and appropriate investigations. Open MedScience does not accept liability for any loss or damage arising from reliance on the material contained in this article. Always consult a qualified radiologist or medical practitioner with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or imaging interpretation.